The ethnic aspect of colonization

The Erzya are a Finno-Ugric ethnic group in Russia's Volga region. Their ancestors have inhabited this region for thousands of years. They call their land the Erzyan Mastor, or “the country of Erzya”. The Erzyan people developed their nationhood between the tenth and thirteenth centuries. Their leader's name, Purgaz, can be found in the Russian Chronicles. Geographically Erzyan Mastor spreads from the Volga and the Oka rivers in the north to the Oka in the west, to the west coast of the Sura river in the east, and to the region of Middle and Lower Moksha in the south.1 In the Middle Ages, the ethnic core of the Erzya was located on the territory of the present-day Nizhny Novgorod region. Large Erzya fortresses were located there. For instance, where the modern towns of Arzamas and Sarov are now (these names are Erzian). However, a Russian invasion dispersed the Erzya people, causing many to flee south. Some were executed, some—Russified. Today the ethnic core of the Ezrya people can be found in the territory of the Republic of Mordovia.

1184 was a tragic yet significant year for Erzyan Mastor. We can call it the year that the colonization of the Erzya began. That year, the Vladimir-Suzdal principality’s invasion of the Erzya lands was first mentioned. According to historical records, the Knyaz of Vladimir Suzdal “set the horses loose” onto the Erzya people. The Vladimir-Suzdal principality started the colonization chain of Erzyan Mastor. The Moscow principality and the Russian Empire were the successors in the colonization project. In 1221, the Nizhny Novgorod settlement was founded as an expansionist vanguard. The modern Erzya and Russian nationals who live in the Nizhny Novgorod region still share legends about an Erzya fortress that was situated in this area. If it did exist, the Vladimir-Suzdal conquerors likely destroyed it. The 1226 Laurentian Chronicles contain more detailed information on the colonization of the Erzya. According to the codex, the Vladimir Suzdal people ravaged part of the Erzya land and enslaved its people. In 1227 Vladimir Suzdal’s Knyaz Yuri destroyed the Erzya dwellings and winter homes. He also ordered the “Russians" (the name found in the chronicle; Russians formed as an ethnic group later) to settle into the occupied Erzya territories, including in the areas of former Erzya settlements. In 1228, Knyaz Yuri invaded the Erzya lands with his army, enslaving and killing the Erzya people, as well as destroying livestock and crops. A faction of Yury’s army followed the Ezrya people into the forest, where, according to the chronicles, they were defeated. In 1229, the Ezrya inyazor Purgaz led a military campaign against Nizhny Novgorod. While the Erzya failed to take the Nizhny Novgorod Kremlin (the main fortified complex), they managed to burn the Holy Mother of God settlement and monastery. In 1232, Vladimir-Suzdal Knyaz once again unleashed his armies on to the Ezrya villages, burning their homes and murdering the people (according to the chronicle, “many Mordovians were slaughtered”).

I believe the facts do not lie: the capture of Erzyan Mastor in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries corresponds to the logic of colonial resettlement. Under this type of colonialism, large numbers of settlers claim indigenous lands and become the majority, to eliminate the indigenous culture(in different ways, from physical destruction to forced assimilation). The Vladimir Suzdal principality did just that. The Knyazes settled lands where the original inhabitants, the Erzya, were either killed or enslaved.

The next stage of colonization began during the reign of Ivan the Terrible. The Muscovite Kingdom conquered the Kazan Erzyan Mastor. In years to come, the Erzya would go on to organize many rebellions against the Russian authorities. During the uprising of Stepan Razin, one of Erzya's leaders was the murza Boleyan Akai. His army that fought against the Czar grew to roughly 15 thousand. However, in 1670 Akai was captured and quartered.2

How colonization affected the Erzya's economic, social, and religious life. Rebelions

To destroy the Erzya’s will to survive, the Russians would burn and settle entire villages filled with children and elderly (for example, the villages Motyzley, Mievley, Oshpire). The territories of Voznesensky and Deveevsky, equal to two modern Novgorod regions, were completely devastated. There are no longer any indigenous Erzya here, except for those who returned in recent years. The Russian colonizers forbade the Erzya from hunting and forging weapons and would further displace them into the woods by seizing and plowing up their lands.3 In newly occupied territories, Russian settlers would build fortifications to prevent the indigenous peoples from reclaiming their homes.

The colonization brought changes to the organization of Erzya society. The famous Erzya ethnographer V. N. Mainov wrote about how the Russification of Erzya included imposing patriarchal traits. Domestic violence emerged in Erzya communities and was used as a “punishment.” Such practices would seem uncommon to the Erzya people. Unlike in Russian folklore, where domestic violence is highly referenced, the stories of the Erzyado do not contain such scenes. In the late nineteenth century, the Erzya would refer to domestic violence as a “Russian tradition.”

The Russian colonizers sought to Christianize the Erzya. In 1629, their nationwide prayer, “Rasken Ozks,” was officially banned. Sacred groves, where the Erzya would hold their prayers, were cut down, and Orthodox churches were built using the wood—that was an invasion of the local ecology.

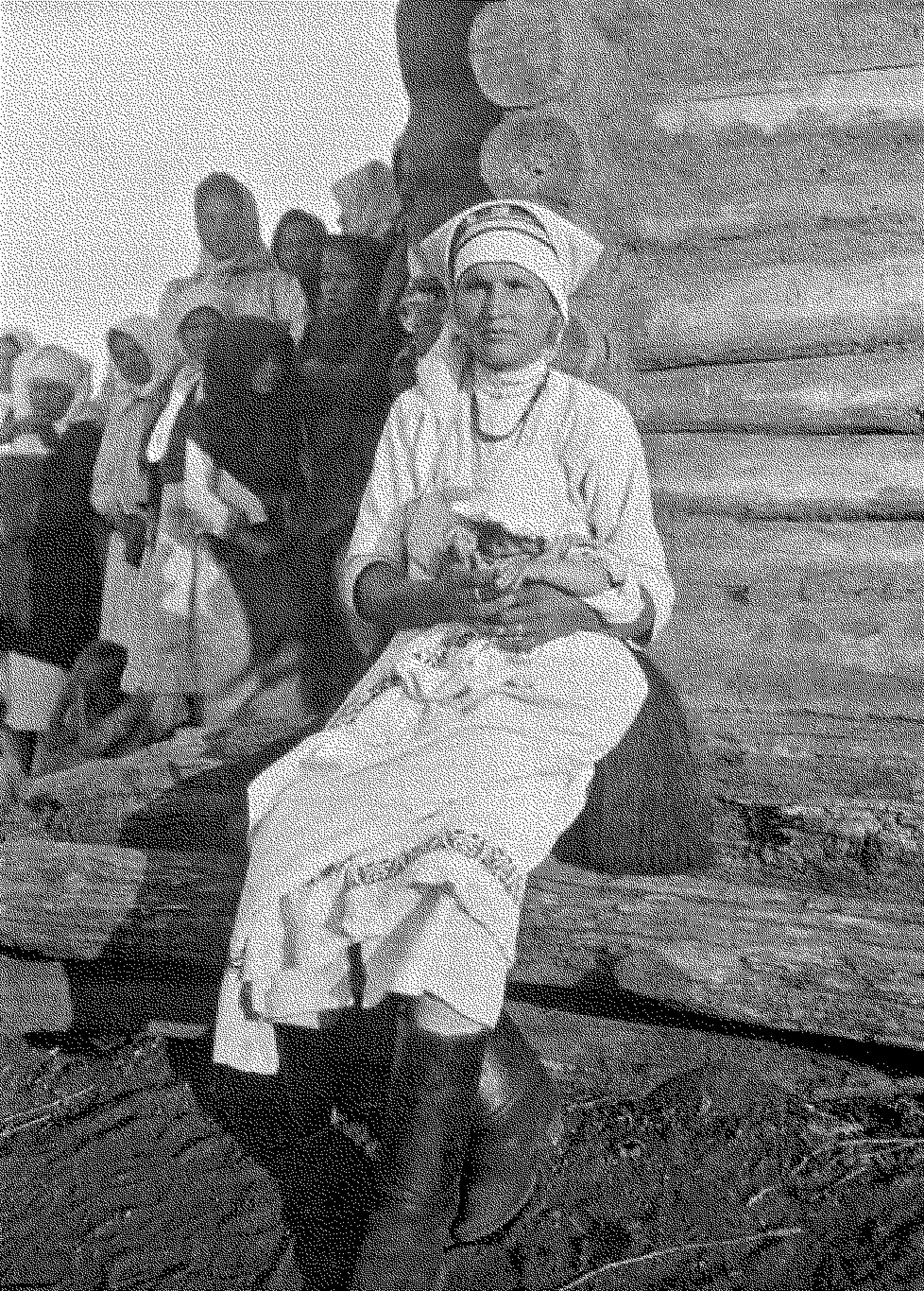

The Erzya tried to resist Christianization and rebelled. The notable Teryushevskoye rebellion of 1743 emerged as a response to a Russian bishop setting fire to an Erzya pagan cemetery. The Erzya attacked the bishop, nearly killing him. Russian authorities responded by suppressing the rebellion particularly cruelly, once whipping a pregnant woman. This further enraged the Erzya, and rebellion broke out again with renewed vigor. Eventually, the rebels fell to the hands of the Czar’s army. Seventy-four Erzya people were killed.4

During the reign of the Russian Empire, one Russifier of the Vilensky region said: “What a Russian bayonet failed to finish, Russian schooling and the Russian pope will.” This saying rings true for many peoples colonized by the Russian forces. According to the goals of colonial resettlement, which are to replace and destroy indigenous peoples, the “Russian bayonet” killed and banished the Erzya from their land, while “Russian schooling” and the “Russian pope” were instruments in assimilating the Erzya through the Russification and suppression of cultural, linguistic and religious identities.

About the USSR period and ethnonym “mordva”

The Russification policy continued into the twentieth century. Despite its formal dedication to equal rights for all and the disapproval of colonialism and imperialism, the Soviet Union continued engaging in colonial practices against non-Russian citizens and subordinate territories, refusing to support national self-determination. For example, in Soviet documents and censuses, it was impossible to use the ethnonym “Erzya”—only the exoethnonym “Mordva” was permitted.

It should be noted that the Russian ethnonym “Mordva” is used to classify two separate ethnicities, the Moksha and Erzya, under one name. The Russian Empire, the USSR, and the Russian Federation sought to forcefully combine two ethnic groups with different languages, cultures, and histories.

Other examples of colonial attempts to eradicate the Erzya identity can be found in translations of Erzyan poetry. In the Russian-language translations of Erzya folk poets, the names “Erzya” and “Erzyan Mastor” (“Country of Erzya”) were replaced by “Mordva” and the “Mordovian region.” Before their forced Russification, the Erzya and Moksha peoples never referred to themselves as "Mordva." Even in present-day Russia, where “Mordva” is still the status-quo classification, Moksha and Erzya peoples continue to distinguish themselves from one another. The Erzya understand that the Mokshans are different people. Once I had the opportunity to hear a dialogue like this between a Russian and an Erzya:

“They are Mordva. I don't know how to find common ground with them.”

“But you are a Mordva too.”

“Yes, but they are Mokshans!”

As part of the struggle for self-determination, during the formation of the Mordovian ASSR, a faction of politicians representing the Erzya and Moksha peoples attempted to create a republic “from below.” Soviet authorities condemned and suppressed this movement, opening a fabricated case against “the Mordovian Autonomist Bureau.” As a result of the trial, seventy members of the Erzya and Moksha intelligentsia were shot between May 23 and 24, 1938. Among those executed was the linguist Anatoly Ryabov, a proponent of the Erzya language and literature. His students were also repressed. The lawyer Timofey Vasiliev, an editor of the Erzyan Kommuna newspaper, K. D. Zvezdin, and the editor of the Syatko magazine D. I. Grebentsov were among the victims as well. Leading figures who were responsible for the revival of Erzya culture and statehood were categorically repressed. Similar cases, all littered with accusations of creating nationalist organizations, were opened across other republics of the Volga region.5

In addition to the physical repression of the national intelligentsia, Soviet authorities launched attacks against the Erzya language. Many terms and phrases with primordial roots that Erzya linguists proposed were replaced with standardized Russian terms. Following orders by the Central Executive Committee Presidium of the Mordovian ASSR, the Erzya terms “teshks,” or “signs,” were replaced with the Russian “znak.” The term “pshkadema,” or, “appeal,” was replaced by the Russian “obrashchenie.” The work of the Erzya linguists was branded as “anti-Soviet.”6

Soviet historians were tasked with depicting the Russian people as a progressive force that “brought light” to the “backward” indigenous peoples. In its section dedicated to the indigenous peoples of the Volga and Ural regions, the Russian Ethnographic museum still to this day characterizes the Russian people as the leaders of history.

The state of the Erzya in modern Russia

While the thesis about the leading role of the Russian people has been reworked over the years, it indeed has remained. Today, the Russian state continues to push the narrative that the Russian people have the right to hold dominion over ethnic minorities. This point of view is supported by the authorities of the Republic of Mordovia. For example, the former head of Mordovia, Nikolai Merkushkin once said that “There are the Russian people, who are the dominant force in this territory, the state-forming [force].” This type of relationship between ethnic groups is cultivated by the state, including by the law. One aspect of the 2020 amendments to the Russian Constitution that went unnoticed by the general public was that the Russian language was named the language of the “state-forming people.” Only activists from indigenous communities took notice of this change.

These repressive policies have unfortunately shaped the psychologies of many Erzya people, who are often ashamed of their non-Russianness. Some Erzya people fear speaking their language in public. Deprived of respect for their own culture, the Erzya people often speak exclusively Russian and refuse to teach their children the Erzya language as a defense mechanism. Such a dynamic creates an unfortunate cultural self-loathing, and many Erzya parents would prefer their children marry into an ethnic Russian family.

In schools, if an Erzya boy makes a mistake during a Russian language class that may be common to a native Russian speaker, a Russian teacher could say, “that’s because he is a ‘Mordva.’” The insinuation here is that the Erzya could be more intelligent and educated. The Indian-British critical theorist calls this the concept of mimicry: the colonizers seek to make the colonized similar to themselves, but not entirely, maintaining a distinction and border between “white” and “non-white.” While the particularities of racism in Russia require separate consideration, an analogy can be observed within the concepts of “Russian” and “non-Russian.”

The policy of suppressing the national right to self-determination continues to this day. At the first All-Russian Congress of the Mordovian people in 1992, initiated by the Erzya group “Mastorava,” Erzya representatives asked to be referred to by their original name “Erzya,” only to face rejection. In 1995, at the First Congress of the Erzya people, initiated by Alexander Malov, Valentin Devyatkin, and Mariz Kemal, a declaration on the official name for the Erzya people was adopted. The Erzya appealed to the authorities with a desire to be accepted “in the world community of peoples under” their “own name.” This demand was also ignored. In 2012, activists Bolyaen Syres and Eryush Vezhai picketed at the Sixth Convention of the Finno-Ugric Peoples World Congress against the Russian authorities’ decision to not allow the admission of a separate Erzya delegation.

The Russian Federation continues to persecute an Erzya national movement actively. For example, in 2007, the General Prosecutor’s office of the Republic of Mordovia launched a lawsuit against the independent Erzya newspaper Erzyan Mastor for creating the Foundation for Saving the Erzya Language in the name of A.P. Ryabov. Authorities accused the newspaper of extremism and of inciting ethnic hatred. The trial ended with Russia’s Supreme Court ruling out any extremism in the newspaper’s work. While the newspaper was saved, on September 25, 2009, police tried to stop aninyazor elected by the Erzya, Kshumantsyan Pirguzh, from handing out copies of the Erzyan Mastor newspaper at the Fourth Congress of the Finno-Ugric Peoples. Pirguzh explained to the authorities that the newspaper is an officially registered publication and does not contain anything prohibited in its publications. However, on September 26, when Kshumantsian Pirguzh was handing out the newspaper again, police detained him. Inyazor was not released until the end of the congress, even after suffering a hypertensive crisis in his cell. A hypertensive crisis can be life-threatening, and hospitalization is mandatory. The police allowed doctors to see Kshumantsian Pirguzh but did not allow him to be transferred to a hospital.

In 2015, another attempt was made to shut down the Erzyan Mastor newspaper, this time by Roskomnadzor, the Russian media watchdog. The Supreme Court of the Russian Federation initially dismissed the claim. However, in 2020, both Nuyan Vidyaz, who registered the Foundation for Saving the Erzya Language in 1995 and was editor-in-chief of Erzyan Mastor and Kshumantsyan Pirguzh, were expelled from the Foundation. The Foundation renamed itself the “Mordovian Republican Social Foundation for the Preservation and Development of the Erzya Language.” The new owners of the foundation believed the previous name was too “aggressive.”

The government-controlled press for the Republic of Mordovia is conducting an active smear campaign against the leaders of the Erzya national movement, particularly Kshumantsyan Pirguzh and the new inyazor Bolyaen Syres, who was elected in 2019.

The Russian authorities also repeatedly tried to disrupt the revived Erzya prayer of Rasken Ozks. For example, they detained Kshumantsyan Pirguzh, who initiated the idea of reviving the prayer, and one of its organizers. Authorities sought to replace Erzya prayer with Russian-language pop music performances.

The Erzya language is also struggling for survival. The United Nations classifies it as an endangered language, and no children learn it as a native tongue. The usage of Erzya language is extremely limited. In Mordovian kindergartens, children and teachers only speak Russian, and only three to four percent of local children learn the Erzya language at home. Beyond the Republic of Mordovia, the language does not exist. Schools lack the compulsory study of the Erzya language, but even Russian history textbooks lack any mention of the language. Finding the right books in Erzya, especially printed ones, can sometimes be an exciting adventure. Even in a bookstore in Saransk that contains Erzya editions, classics or dictionaries in the language can not be found. The only Erzya-language children's magazine, “Chilisema,” is in danger of closing down due to its incredibly low readership. Today, even many Erzya settlements bear Russian names. It would take a monumental effort to rename these settlements, and, as a result, Erzya names are gradually falling out of use.

The Russian colonialist machine also actively distorts and suppresses the history of indigenous peoples. In the center of Saransk, there is a square dedicated to the “millennium of the unity of the Mordovian people with the peoples of the Russian state.” The monument’s inscription suggests that the Mordovian people are united with the ancestors of the Russians, who, eight hundred years ago, killed and enslaved the Erzyan people.

Another example: in the eighteenth century, the founder of The Monastery of the Dormition of the Mother of God, hieroschemamonk John, claimed that perhaps it could have been an Erzya city located on the site. Russian scholars at the time dismissed this claim. In their eyes, Erzya culture was, apparently, too low-brow. Only in the 1990s, thanks to excavations, the existence of an Erzya fortress was recognized, but not instantly and not without difficulty.

The policies stemming from Russian colonialism are leading to the rapid decline in Erzya. From 2002 to 2010, Erzyans and Mokshans decreased by almost 100,000. During a speech at the United Nations, the inyazor Bolyaen Syrescharacterized Russia’s actions as ethnocide against indigenous peoples. This was the first time in history that a speech was delivered to the UN in the Erzya language. The Ukrainian delegation provided the opportunity to speak.

Solidarity with Ukraine

Bolyaen Syreshas lived in Ukraine for a long time. His desire to actualize his ethnic and national identity was born from an acquaintance with a Ukrainian politician and Soviet dissident Vyacheslav Chornovol, who spoke to him in the 1990s in Kyiv. Syres was impressed by Vyacheslav Chernovol’s extensive knowledge about the Erzya people. The Ukrainian dissident learned about the Erzya people during his time at the labor camps in Mordovia. At the beginning of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Inyazor joined the Ukrainian territorial defense. While there are Erzya volunteers defending Ukraine, Inyazor says that there are still too few to form a national legion of their own. However, a faction of the Erzya national movement opposes Russian aggression in Ukraine. In 2014, the executive committee of the Erzya people’s Congress issued an appeal on the inadmissibility of sending Erzya to war in Ukraine. And in 2022, the inyazor from Kyiv called on the Erzyans to take to the streets and stop the war.