A fateful expedition

In 1913, a scientific expedition set out from Krasnoyarsk with the goal of studying the soils and ecosystems of Tuva, then known as the Uryankhai Krai[1]. The expedition team consisted of soil experts, botanists, ornithologists, and a photographer-ethnographer, Vladimir Petrovich Ermolaev[2]. The expedition was funded directly by the Russian Academy of Sciences and carried out by Russian scientists tasked with studying the economic potential of a future colony. It is important to note that Russia will annex Tuva in 1914 as krai. Tuva’s self-governance will be exercised through feudal Noyons were the governing class appointed by Mongol feudals in Qing Dynasty. collaborating with the Empire[3].

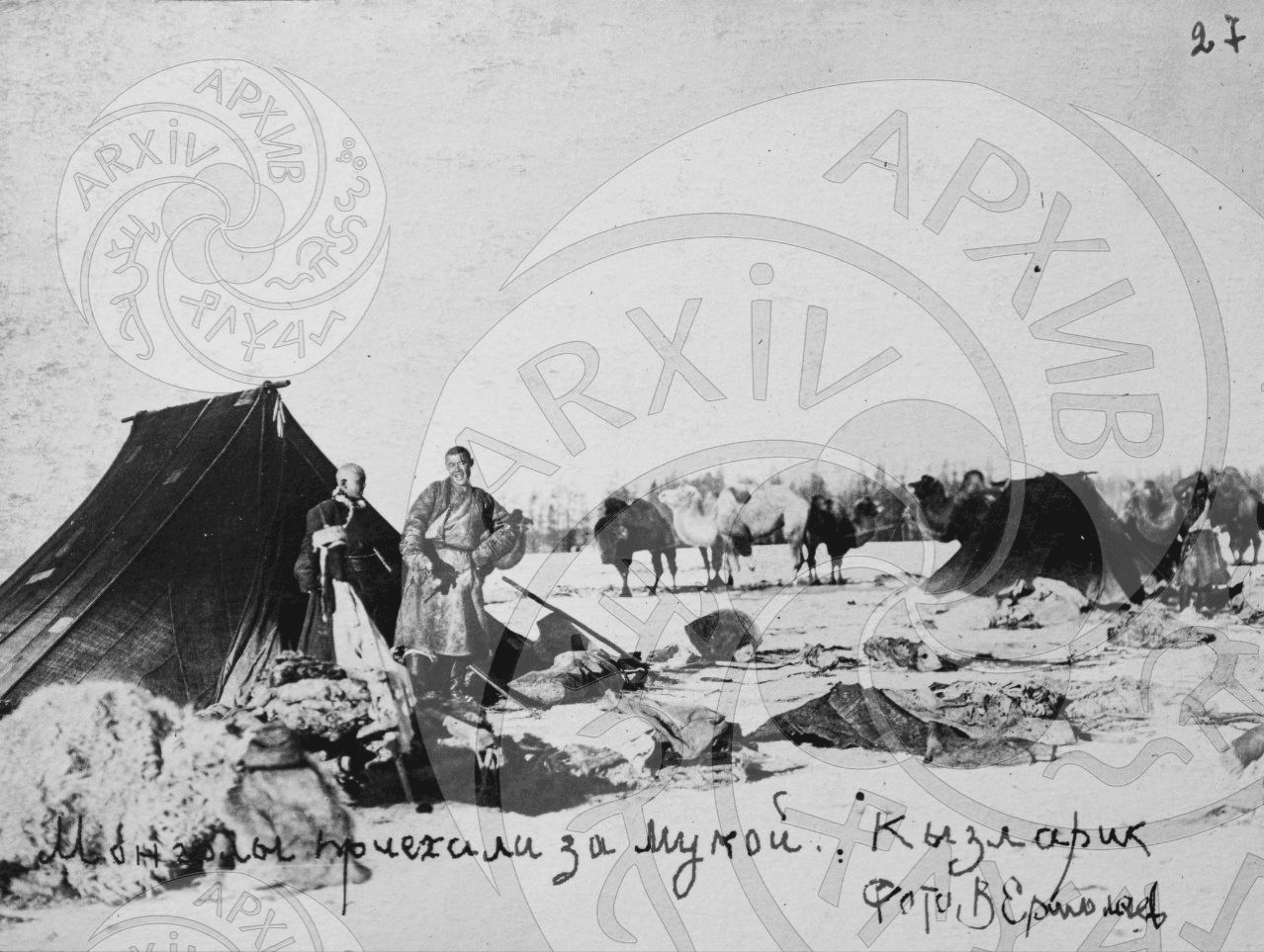

Although the empire’s interest in colonizing Tuva had emerged earlier, as evidenced by the notes of Russian merchants from the late 19th century[4], this expedition represented a more comprehensive study of Tuva by a professional scientific team, following the ethnographic expedition by Pyotr Ostrovskikh in 1897. During this period, such colonial expeditions when European scientists studied colonies, were conducted in various imperial contexts. Their key goal was to investigate the extractive base of the region. In the case of the 1913 expedition to Tuva, it can be assumed that the Academy wanted to study the mineral base, possibility to grow various crops, and to document “exotic” species. The photographs could serve as the evidence of observations regarding soils, for instance, in Elegest, Pii-Khem and Tandy.

In the future, the TAR (Tuvan Arat is a Tuvan word for peasant who is involved in pastorial lifestyle. Republic), a satellite state of the USSR, will base its economy on agriculture on collective farms, gold-mining by “artels” from the USSR, and the sale of fur[5]. Does this mean that the 1913 research could have been pivotal for Tuva’s fate, including the years after the 1944 annexation? What can the photo archive of a 1913 scientific expedition tell us about the key events in 20th century Tuva?

The Ethnographer from Krasnoyarsk

Vladimir Petrovich Ermolaev was born in 1992 in the village of Kansko-Perevozinkskoye, which was later renamed Kan-Perevoz, and, in 1947, became part of Kansk town[6]. In 1910, Vladimir began working at the Krasnoyarsk Regional Museum. It was there in 1913 that the Norwegian traveller Fridtjof Nansen visited, as he was interested in studying the North. Prior to his trip to Krasnoyarsk, Nansen had led an expedition to Greenland (1888-1889), after which he wrote about the need for the “decolonization” of Greenland, arguing that the local Inuit lived in a state of “communism”, and that Danish “progress” was destroying the Indigenous people and island[7].

In gratitude for the assistance, Nansen gave Ermolaev a fateful camera, which he would use from 1913 to 1938 documenting Tuva and creating a visual narrative. In 1916, before the revolution, Ermolaev moved to Tuva to study the local people and their way of life. In 1929, he became the director of the first State Museum of Tuva[8], which he also filled with exhibits from the Hermitage and the Russian Museum. He would work at this museum for practically his entire life, until 1974, forming the collection displayed today in the National Museum of Tuva. Throughout his life, he was engaged in photography and at different periods donated his work to Tuva’s archives. After his death, the State Archive of Tuva received a collection of 4000 negatives and photographs[9]. Today, the State Archive has digitized 13 main albums that cover first annexation and TAR periods[10]. These albums are titled in accordance with narrow themes, and many preserve original titles and descriptions. By studying narratives in these albums, one can understand how Soviet modernization happened in Tuva and see what social, environmental, and economic dimensions were noted by first generations of Russian-Soviet settlers—a group to which Ermolaev belonged.

“Nature”

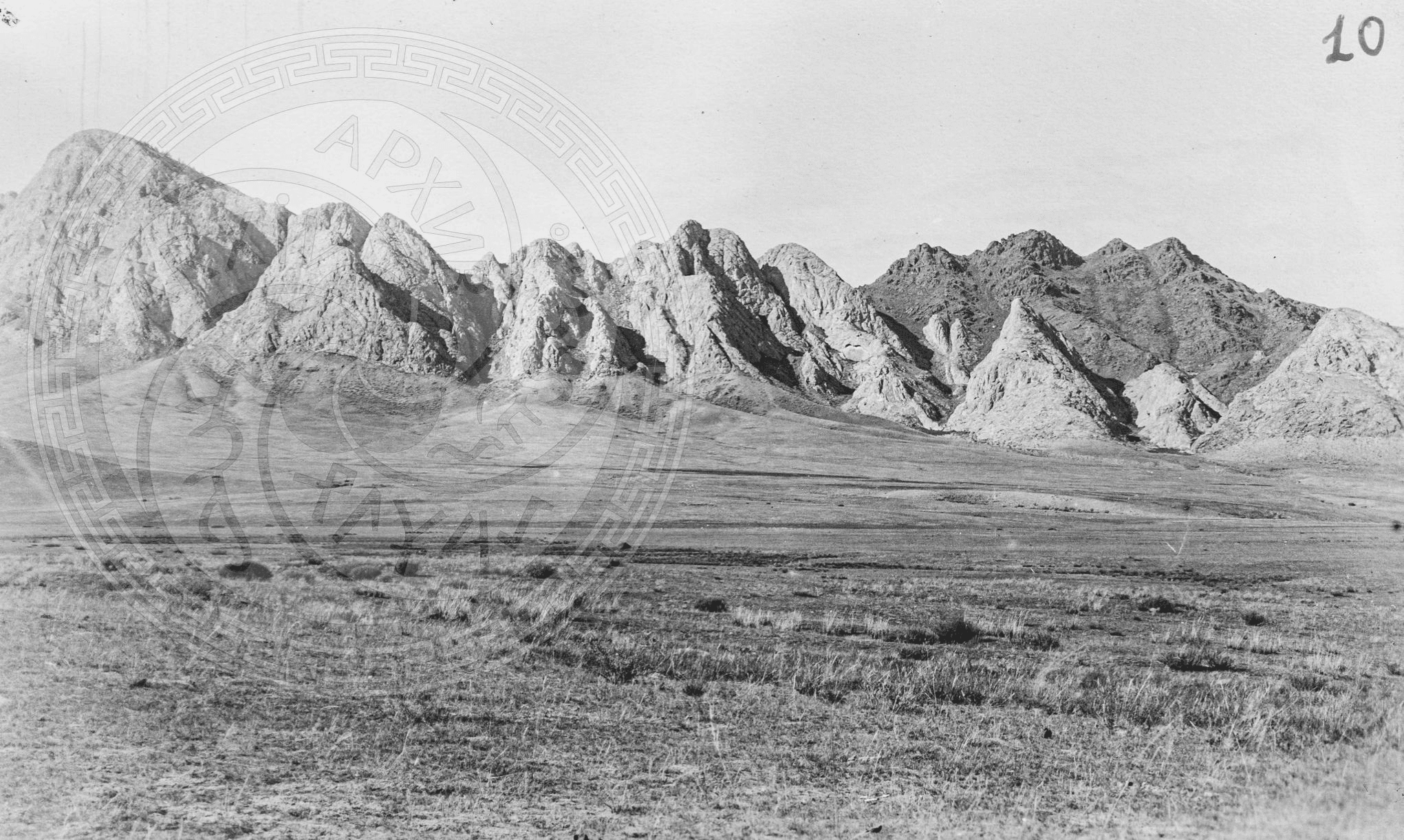

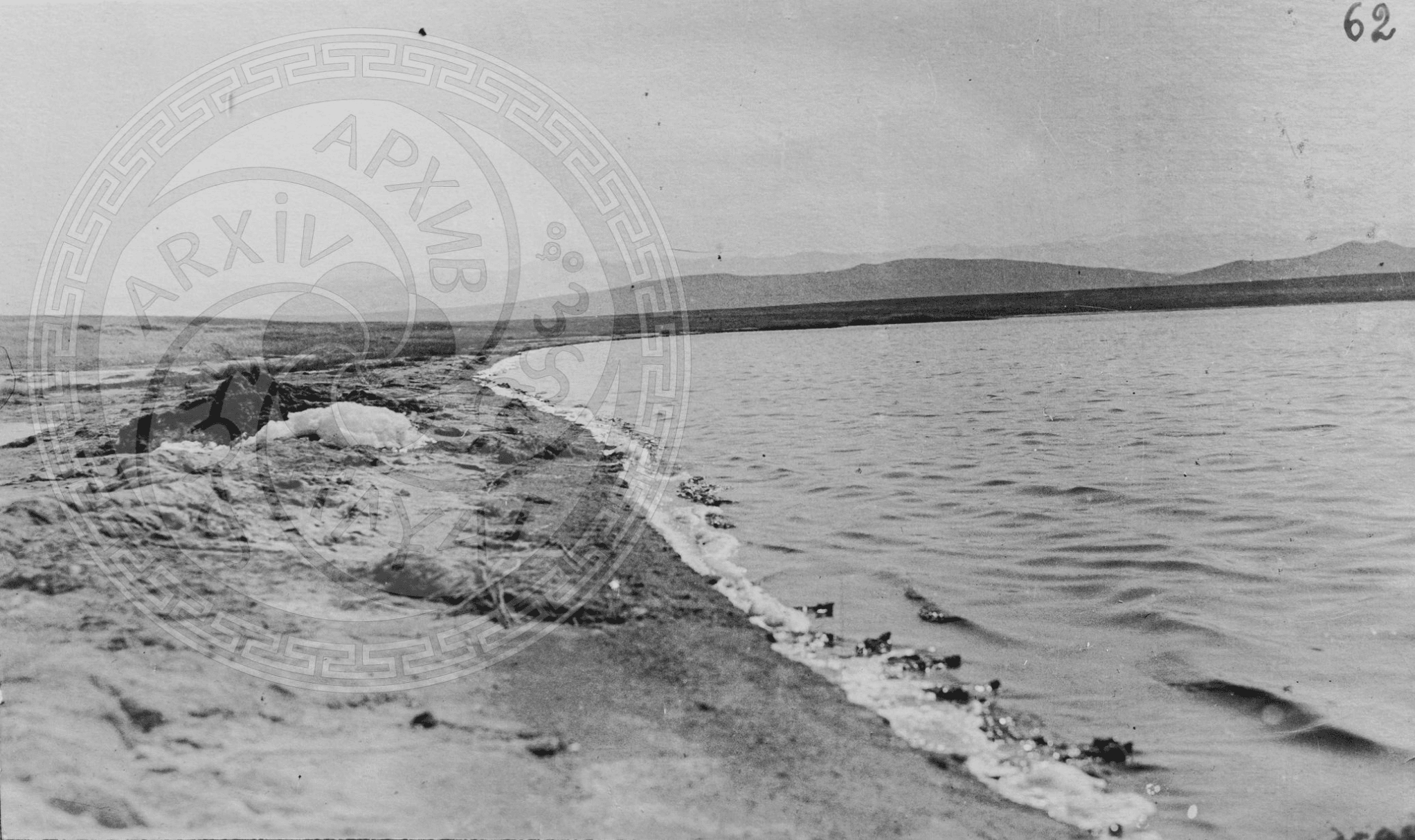

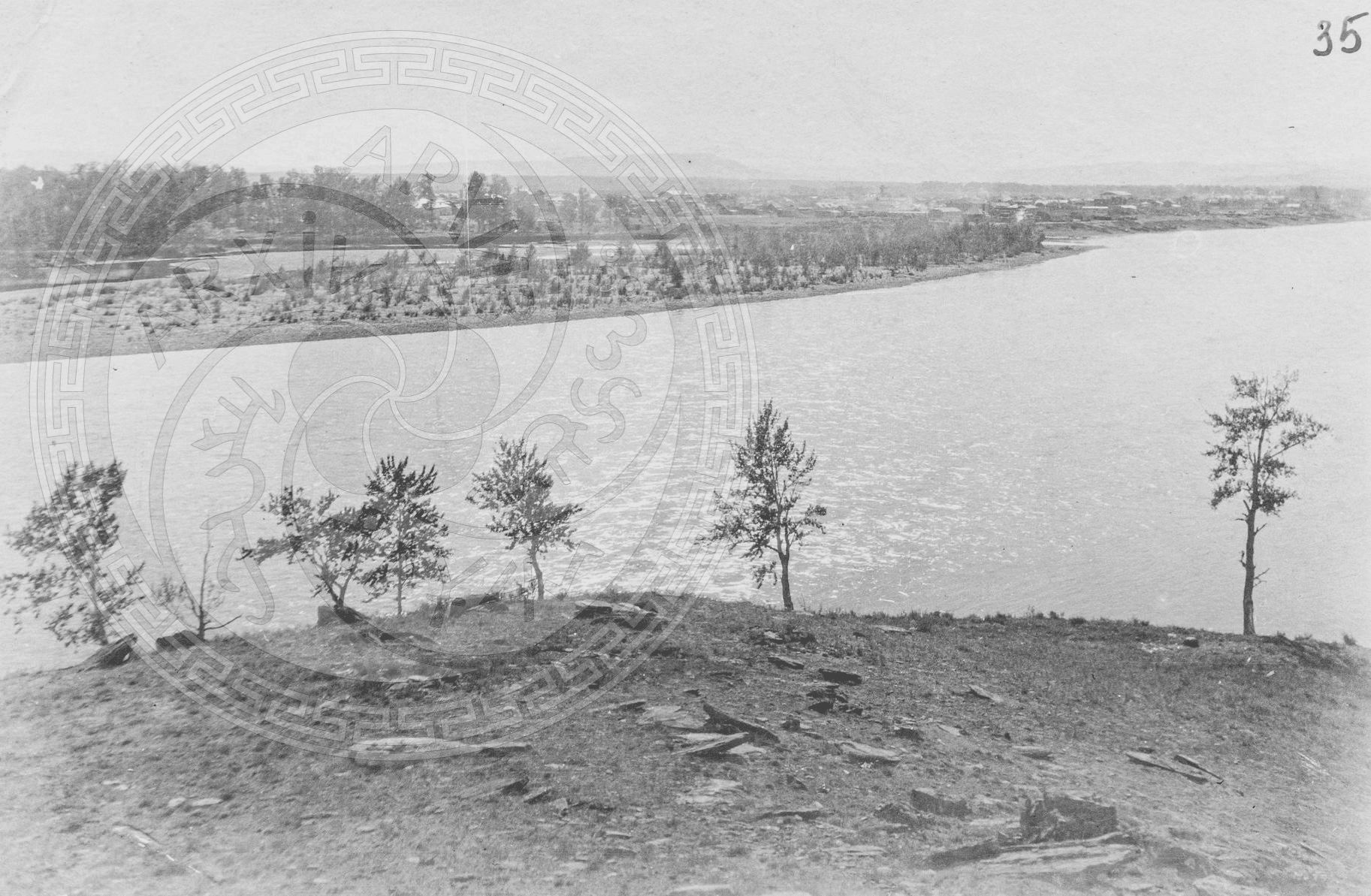

Ermolaev’s earliest photographs, taken during the 1913 expedition and later, reflect the research goals of his colleagues. There are numerous shots of landscapes: mountains (Khayyrakan, Sayans, Tandy, Bai-Taiga), rivers (Yenisei, Alash, Pii-Khem, Uyuk), and lakes (Chagytai, Azas, Khadyn, Tore-Khol). The geography of these photographs captures kozhuuns where Russian Old Believer settlers fleeing Russia in the 19th century primarily resided. Thus, among the photographs, one can see lakes Khadyn and Chagytai located near Tandy Range where Russians plowed the land and founded their communes. This archive also includes landscapes of the Yenisei River, particularly the Great Yenisei (Bii-Khem), along which Russians had also settled in the late 19th century.

One of the photographs offers a view of the basin where Pii-Khem and Kaa-Khem merge, forming Ulug-Khem, the Yenisei. The photograph was taken from a spot called Khem-Beldir, which means “river confluence” in Tuvan. In 1914, the first official Russian colony, Belotsarsk, would be established on this very site by order from St. Petersburg. It was later renamed Kyzyl[11]. Ermolaev foresaw the fate of this capital city drawing attention to the strategic importance of this location, which lies in the center of the present-day republic and also provides access to the waterway to Krasnoyarsk. The city of Kyzyl would appear repeatedly in his later archives, as it became the stage for a series of historical events that would lead to the second annexation of Tuva in 1944.

At a Crossroads

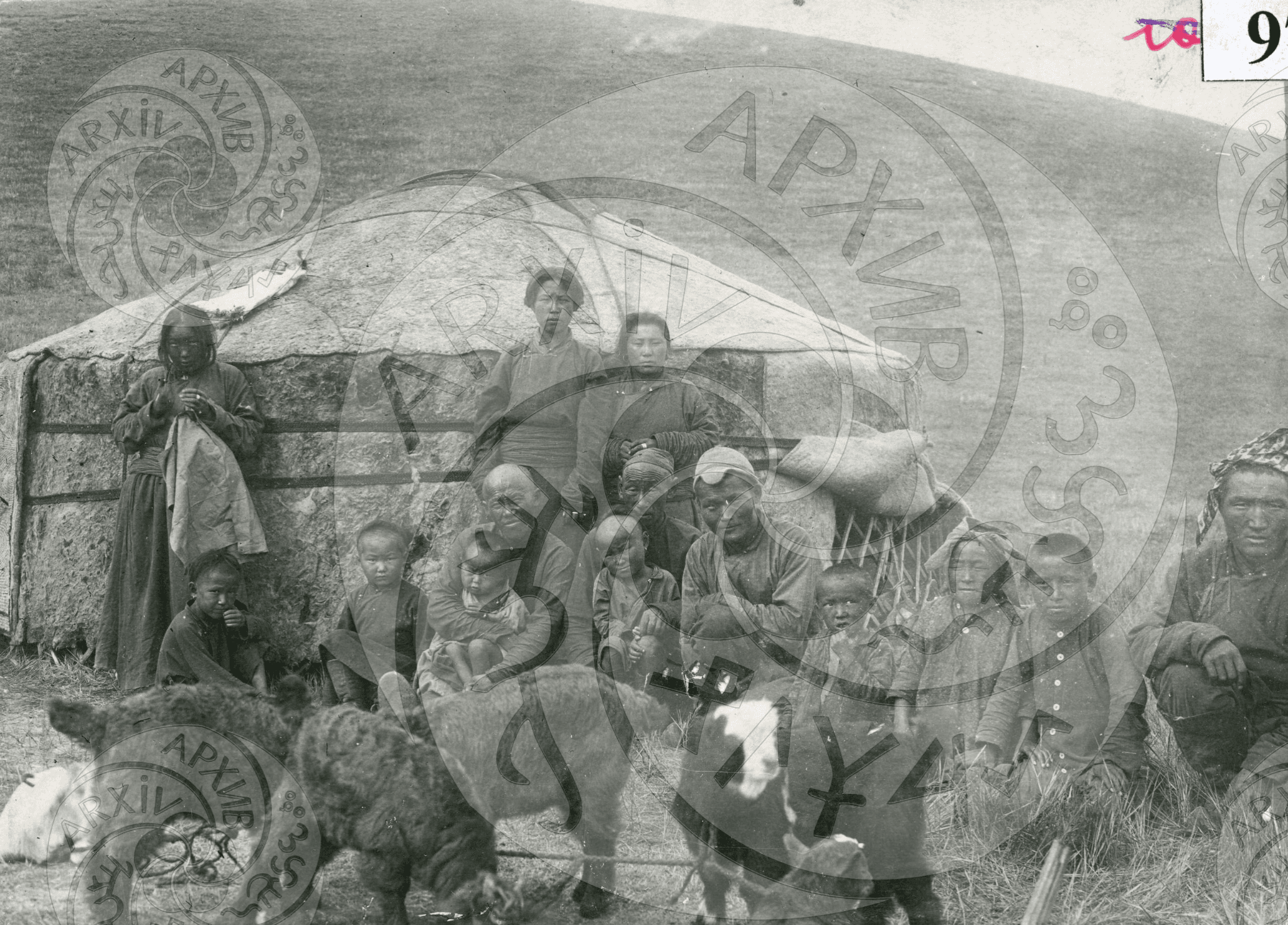

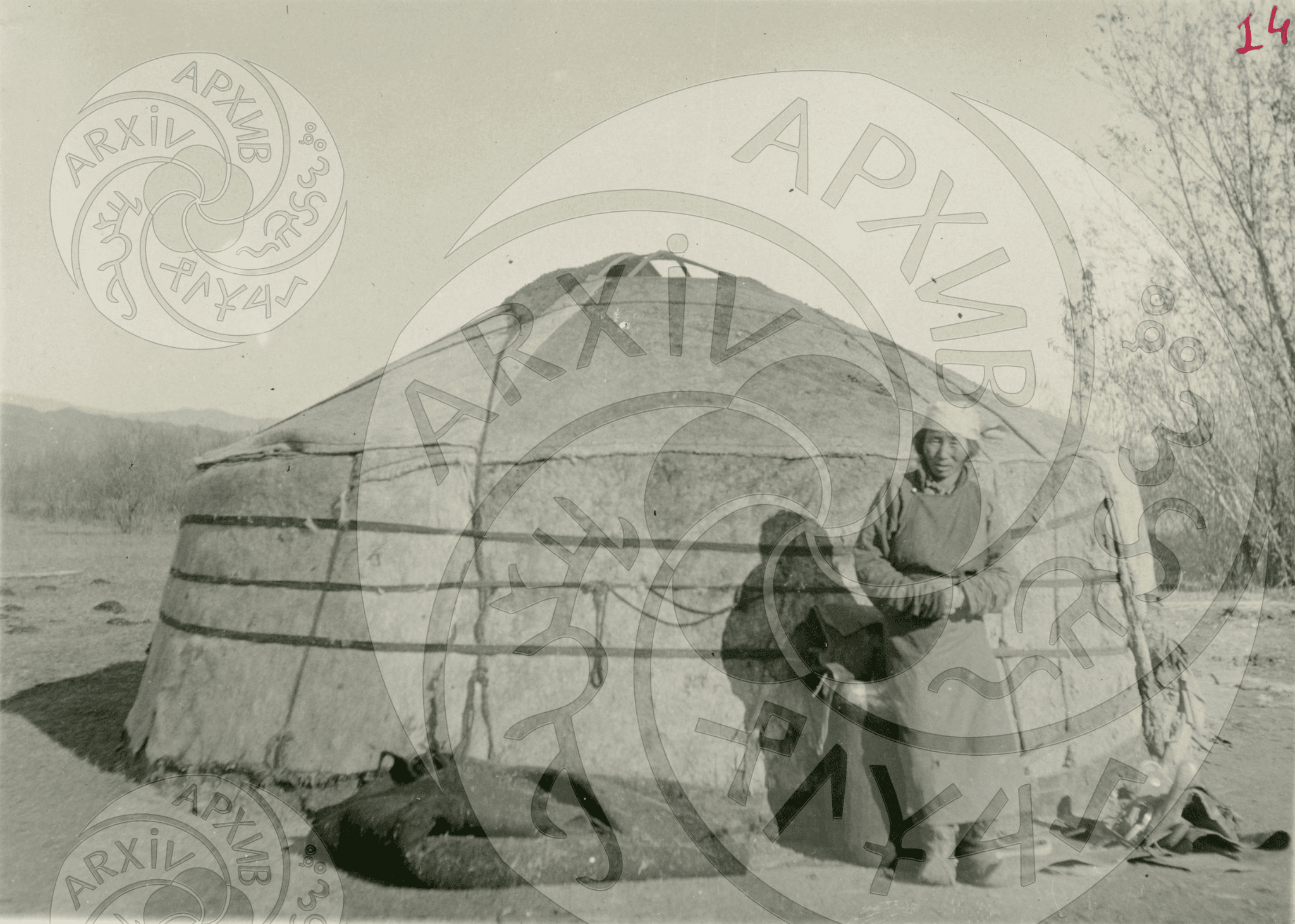

The later albums, which are grouped thematically in the archive, witnessed the abrupt transition that happened in the TAR, specifically in its earlier period. For example, albums No. 6-8, labelled “Trade, Crafts, and Transport” show how socialist modernization transformed many traditional practices12-13. A clear example of such radical changes is the state farms (goskhozes) that replaced the nomadic pastoral economy, which was based on family labor. Photographs of milkmaids, haymakers, and new types of livestock (pigs, morals) imported from the Soviet Union were taken during the same period along with Tuvans who continued the nomadic way of life. The archive contains photos of children by their yurts and various livestock of Tuvan families.

Domestic space also transformed. In the archives from the 1920s, one can see families living in yurts and chums in some photos, while in others, sedentary types of housing are already being conducted, mostly in settlements with major Russian populations, such as the villages of Uyuk and Elegest, and the city of Kyzyl. Furthermore, in his captions, Ermolaev notes the socio-economic status of the people in the photographs, which foreshadows the subsequent repressions of wealthy arats and the campaign against the bai class. Photos of Tuvans in traditional clothing are also found in the same album as Tuvans who adopted Soviet norms of appearance. This is most clearly seen when comparing party officials with those Ermolaev labeled as “wealthy arats,” even though these people lived roughly at the same time.

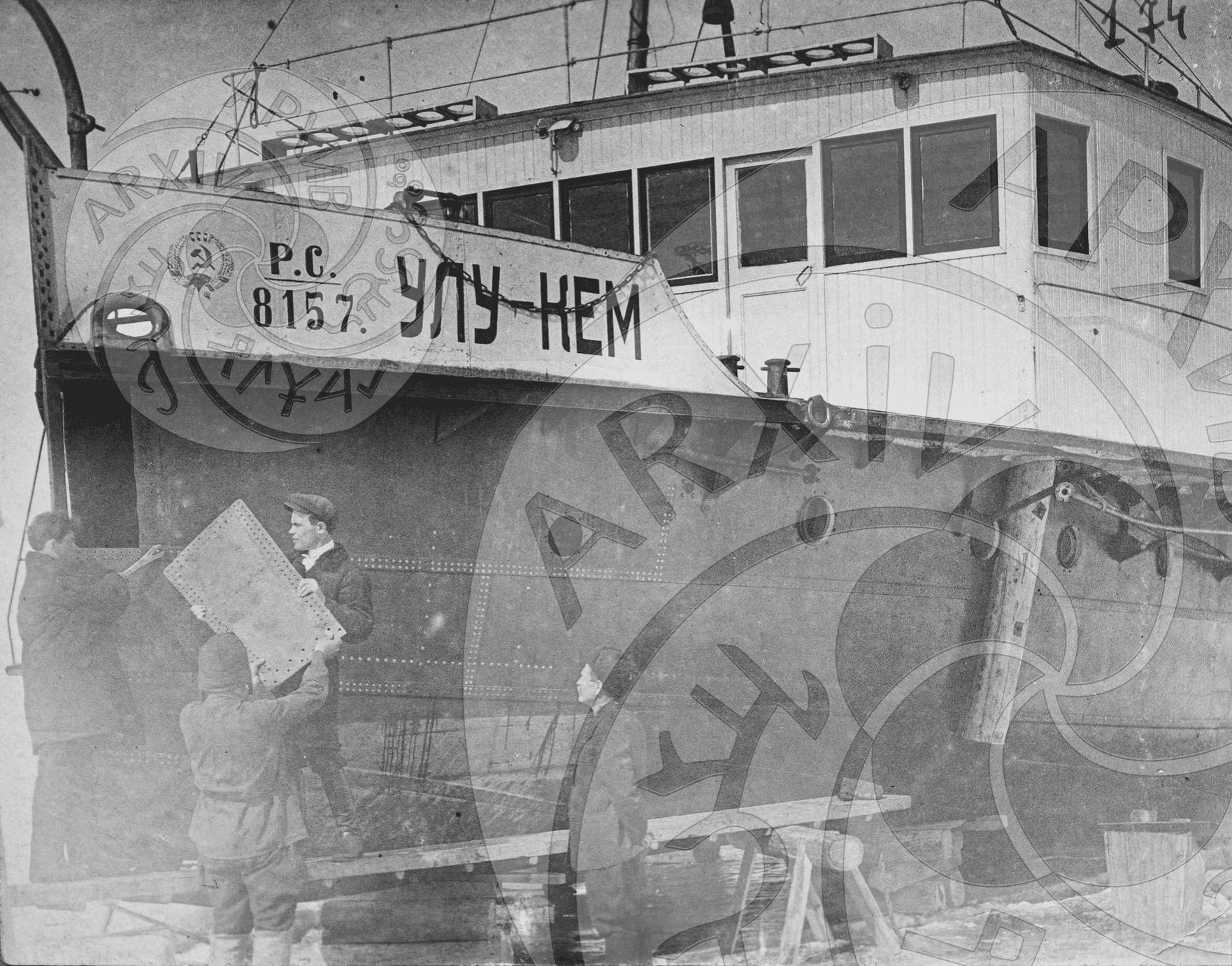

The transport and logistics deserve special attention in Ermolaev’s albums. During the TAR period, the republic set a course for closer ties with the Soviet Union, embodied in significant infrastructure projects to connect Tuva and Russia via road networks. The steamships and automobiles that Tuva imported from the USSR become one of the visual narratives in the archive: here, photos of the steamship “Ulu-Kem” and the first cars in Tuva are juxtaposed with images of camels and yaks, which Tuvans used to transport their belongings and undertake long seasonal migrations. In his photographs of road construction between Tuva and Russia, via Elegest and Uyuk, Ermolaev notes the “international” composition of construction crew—interestingly, the Tuvan workers are much younger than Russian ones, and in the photos, they are separated into their own groups.

Festive culture existed in Tuva before the introduction of mass May 1st parades. For instance, one of the most significant holidays in Tuva—before it was banned—was Naadym, the festival of livestock breeders. Traditionally, one of the main spectacles of Naadym was the Khuresh wrestling. Ermolaev's photographs show how this holiday was celebrated before its prohibition and how it was gradually replaced by May 1st demonstrations. Rallies in honor of May 1 are also captured in the albums, but it's important to note their geography: most photos were taken in Kyzyl, where such a demonstration could have been staged. However, the very existence of these photographs signals major future changes, when May 1st marches would become compulsory and mass events, and Naadym would be banned as part of the “feudal” past.

The albums from the 1913–1938 period tell of a pivotal moment in Tuva's history, when the old nomadic order coexisted with new socialist modernization projects. The people, landscapes, and technology in the photographs narrate this sharp transition through a visual language. Many aspects of life changed significantly in the 1920s-1930s, including the economy, culture, and the very essence of what it meant to be Tuvan. No one knew what would happen next or what future awaited Tuva.

Toka and the Future Repressions

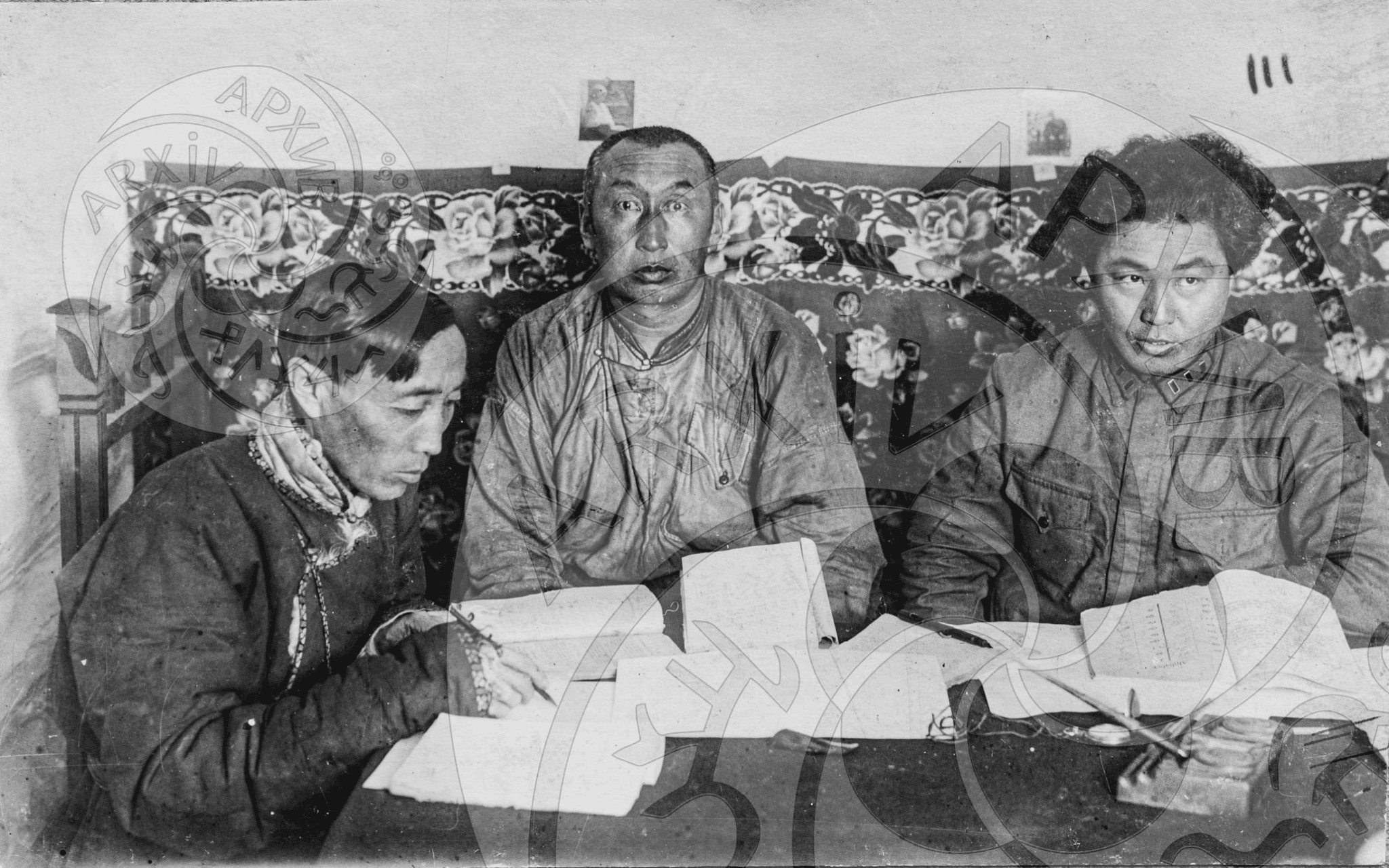

In albums No. 6-10, the beginning of political transformations in Tuva's history quietly unfolds. One photograph captures a young Salchak Toka, the future Stalin-influenced dictator, while another shows him with officials of the TPR Government, such as Sat Churmit-Tazhy, Chairman of the TAR Council of Ministers. Most of the people in these photographs would be repressed by Toka in the 1930s, and in 1944, Toka would single-handedly annex Tuva to the USSR. Sat Churmit-Tazhy and other ministers also present in the photos would be repressed in the fabricated “Case of the Nine.” They would be accused of allegedly acting as agents for Japan, which was considered a common enemy of the TPR and the USSR at the time[14]. The photographs also feature many graduates of KUTV—the KUTV is a higher educational institution that operated in Moscow from 1921 to 1938, where students from the USSR studied, from whom they were supposed to prepare producers for the nomenklatura of the Soviet republics, as well as foreign students who later led the efforts to establish communism in our countries, organizing uprisings and revolutions.—who would play a significant role in Tuva's future. For instance, in one photo, Toka is sitting next to Tanya Sat, the first TAR ambassador to Mongolia.

The photographs also show traders from Mongolia, China, and Korea, who came to Tuva either to acquire goods like hay and furs or to sell their own. Most of these visiting traders would also be repressed or expelled from Tuva under Toka's leadership. Thus, Tuva's participation in the international economy would decline, ultimately leading to the idea that Tuva could only engage with the outside world through the “big brother.”

Ermolaev also managed to photograph Buddhist monks, the interiors of Chadan temples, and lama students. All of Tuva's temples would be destroyed under Toka's anti-religious agenda, which was inspired by the repressions in the Soviet Union. Ermolaev's archives even contain photographs of lama congresses where questions of uniting Buddhist philosophy with socialist modernization were discussed. One photograph shows the creator of the first non-Mongolian, Latin-based alphabet for the Tuvan language, Teacher Lopsan-Chimit. He too would be repressed in the main wave of anti-religious repressions, and his alphabet project would be replaced by a Cyrillic one created by A. Palmbakh, a linguist from the USSR[15].

Among the photographs of the Tuvan Government, the figure of Mongush Buyan-Badyrgy, known as the founder of Tuvan statehood, stands out. It was he, as the first leader of the TPR, who sent the young Toka and his colleagues to KUTV to gain experience for modernizing Tuva along the Soviet model. However, Toka would return from Moscow with different goals, and his mentor, Buyan-Badyrgy, would also become a victim of brutal repression.

Kyzyl and its Sovietized space played a special role in Toka's rise as the primary agent of the aggressive Soviet modernization that would follow the 1944 annexation. Urbanization was presented as a necessary part of Tuva's industrialization. The photographs show factory production precisely in Kyzyl—for example, a tannery or a bakery. It was in Kyzyl that Soviet-Tuvan fairs were held, where the manifestation of the Russian extractive economy was most vivid. The photographs show an abundance of furs, which—both in the Russian Empire and the early TPR—were a valuable commodity.

***

Ermolaev's archive captured Tuva at its pivotal moment—before the mass repressions, aggressive collectivization, and the strengthening of USSR influence. It tells the story of how individuals became puppets of an empire, of the coexistence of different economies and ways of life, and of how modernization radically transformed everyday existence.