In the 18th century, Germans began emigrating to the Russian Empire to avoid military conscription, religious persecution, and the harsh economic consequences of wars. The German diaspora became tightly integrated into the economic and cultural life of the empire. But in the 20th century, they faced a tragic fate as German farmers, scientists, politicians, and entrepreneurs were labelled “enemies of the people.” In this article, I will recount how Germans ended up in the Russian Empire, how their reception changed, the history of the German republic within the USSR, and how Germans ended up in the Soviet Empire’s Central Asian republics.

While telling the history of the German diaspora, I will also share the story of Eduard, a German born in Kyrgyzstan who repatriated to Germany in 1989 at the age of 10. Eduard lives and works in Germany, speaks Russian, remembers the USSR, knows a lot about Kyrgyzstan, and likes to travel around it in his minivan. I met Eduard during one of his trips, where he told me his family story and shared archival photos with me.

How Germans Came to the Russian Empire

In 1762, Empress Catherine II signed a manifesto entitled “On allowing foreigners to settle in Russia and the free return of Russian people who fled abroad.” The manifesto read:

And as many foreign subjects of Ours, as well as those who have left Russia, have made a favorable report to Us that We allow them to settle in Our Empire: We hereby Most Graciously declare that not only foreigners of various nations, except Jews [Until the 17th century, the word “Zhid” did not have a pejorative connotation in the Russian language and was used as a neutral ethnonym. However, in 1787, Shklov Jews appealed to Catherine II with a request to remove the offensive term “Zhid” from official usage. (Western Suburbs of the Russian Empire. Edited by A.I.Miller and M.D.Dolbilov. Moscow: New Literary Review, 2006.)],are accepted with Our usual Imperial favor for settlement in Russia, and We most solemnly affirm that all those who come to settle in Russia will be granted Our Monarch's mercy and favor, but that We also allow the subjects who have heretofore fled from their fatherland to return.

In other words, Catherine II invited all foreigners to the Russian Empire, with the exception of Jews, who later became Russian subjects involuntarily, due to the three partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1772, 1793, and 1795, respectively.

According to the manifesto, foreign colonists were granted certain privileges. For example, they were exempt from taxes for 30 years if they settled in the “free” lands — tracts in Tobolsk, Astrakhan, Orenburg, and Belgorod Provinces, lands around Saratov up and down the Volga. These were the Russian Empire’s “new territories”, the Volga region which it had seized two centuries earlier after devastating campaigns against the Khanate of Kazan and Astrakhan.

Creating narratives about “free” or “empty” land is a perpetual rhetorical device of colonial powers. These lands were not in fact “empty”. They were inhabited by various indigenous peoples: Turkic, Oirad (Kalmyks), and Finno-Ugric. Finno-Ugric groups — Moksha, Erzya, Mari, and Udmurts — have inhabited the Volga region since ancient times. In the Middle Ages, Turkic nomadic groups began to penetrate the region, later developing into the Khazar Khanate, Volga Bulgaria, the Golden Horde, Kazan, and the Astrakhan Khanate, and playing a major role in the ethnogenesis of the Tatars and Chuvash peoples. In the 16th and 17th centuries, Oirad-Kalmyks began to migrate to the region from Dzungaria.

The indigenous peoples in the captured lands resisted colonization, often through military action. The colonial authorities perceived the liberation struggle of the Oirad-Kalmyks, Tatars, Bashkorts, and other peoples of the Ural-Volga region as a hindrance to effective governance. In 1719, Kazan Governor Artemiy Volynsky wrote:

Between the cities of Saratov and Astrakhan for more than two hundred and three hundred versts there is no life. Therefore, both merchants, other travellers and fishermen are subjected to great destruction by the Kalmyks and Kubans, and workers are taken prisoner.

Peter I’s policies for strengthening imperial power in the Volga region included forced Christianization of the entire local population, depriving Tatars in his service of their previous privileges, increasing taxes, and other repressive economic measures. By the mid-18th century, these measures Nogmanov A.I. Petrovskie. Transformations in the Middle Volga Region (on legislative materials // From the History and Culture of the Peoples of the Middle Volga region. 2022. Т.12, №4, pp. 68–80. [Ногманов А.И. Петровские преобразования в регионе Среднего Поволжья (по материалам законодательства) // Из истории и культуры народов Среднего Поволжья. 2022. Т.12, №4. С.68–80.] and the authorities started actively “developing” the region.

Catherine II’s administrators saw the agricultural potential of the Volga region’s fertile soil. This made Catherine particularly active in recruiting colonists from what is now Germany, where agriculture was better developed at the time to improve agriculture in the conquered lands. Colonists were considered more loyal to the empire than the conquered local populations. After all, in exchange for their loyalty, the empire granted them numerous privileges that they, as members of oppressed religious minorities, had been denied in the places they left.

The colonists were exempted from paying taxes, promised interest-free loans to build houses and buy equipment, as well as compensation for travel expenses, full self-government in the colonies, and freedom of religion. For Eduard's Mennonite ancestors, freedom of religion provided an impetus to immigrate to the Russian Empire. Mennonites are a Protestant religious movement that emerged in the 1530s in the Netherlands during the Reformation. Mennonites were principled pacifists who refused to take up arms and fight due to their religious beliefs.

Because of this, they were considered enemies not only of the church, but also of the state, and were actively persecuted in the Netherlands, the Holy Roman Empire, and Prussia.

In the 18th century, Prussia was a militarized state that fought numerous wars and invaded neighbouring lands. The country's ruler, Frederick William I, was even nicknamed the Soldier King. Prussia also tried to draft Mennonites into the army, where the term of service was 20 years. To escape the draft, they travelled to the Russian Empire, which is how Eduard's ancestors, who lived in the north of what is now Germany on islands that border the Netherlands, ended up there.

However, even in the Russian Empire, the religious freedom of Germans was restricted by the caveat that their religion did not “infringe on the interests” of the Orthodox Church. Germans could build churches and have pastors only where the majority of the population was of their faith — that is, only in their colonies. In addition, they were forbidden from proselytizing among the Orthodox. But at least in the Russian Empire, they were not drafted into the army — in any case, not at first.

Mennonites, Lutherans, and other Protestants, as well as Catholics, travelled to the empire. The Peace of Westphalia, which ended the Thirty Years' War in the Holy Roman Empire in 1648, assigned each locality in Europe its own religious status. The pressure on Protestants who found themselves in Catholic territory (and vice versa) and the economic consequences of the war forced people to emigrate.

In the Russian Empire, Germans settled not only in the Volga region, but also in the northern Black Sea region, Transcaucasia, Crimea, northwestern Ukraine, the North Caucasus, and Siberia. There were conflicts between the colonists and local populations, mostly over land. Sometimes armed groups even attacked German colonies.

The second wave of German migration to the Russian Empire began after Alexander I issued a decree in 1804, “On allowing landlords and land owners to accept and discharge foreign colonists to settle on their lands”. The decree clearly stated the purpose for inviting colonists to the empire:

The benefits and advantages which landlords can expect from the settlement of foreign colonists on their lands are incalculable. Among them are that the number of labourers will increase: fallow lands will be cultivated with excellent skill; the volume of produce will increase, and, what is most advantageous of all, farming, produced by skilled and knowledgeable workers, will spread from the colonists to other settlers.

By 1897, German colonists comprised 1.4% of the population of the Russian Empire. To compare, in 2020, the percentage of the German population in Russia was no more than 0.13%. The empire’s German population was numerically comparable to the population of an entire country — for example, Latvia in 2024. Some of the Germans became so deeply integrated that today they are often mistaken for Russians by people unaware of their German origins. Among them are Denis Fonvizin, Pyotr Struve, Mikhail Barclay de Tolly, and other Germans who contributed greatly to the country’s development.

Germans in the Service of the Russian Empire: Instrument of the Authorities, for Indigenous People — Landgrabbers

In the Russian Empire, Germans occupied a dual position. On the one hand, they were privileged in relation to both indigenous peoples and Russian peasants. Germans often received the lands of exiled peoples who, in the case of nomads, had been deprived of the seasonal mobility. The regime seized lands and distributed them to nobles and those in the tsar’s service in the Urals, Siberia, Kyrgyz steppes, Priamurye, and Transcaucasia.

On the other hand, the Germans were used by the authorities as a tool that helped strengthen the empire’s agro-economy. Germans introduced the plow, the scythe, and wooden threshing machines, which had barely been used in Russia previously. German colonies became major suppliers of wheat, rye, oats, barley, flax, hemp, tobacco, and potatoes. German colonists developed the industry, producing flour, oil, agricultural implements, wool, leather, and fabric. An especially powerful weaving industry had developed in the colony of Sarepta, with sarpinka fabric named after the colony.

However, starting in the mid-19th century, Germans were gradually stripped of their privileges. In the 1860s, Alexander II introduced compulsory military service for them and German colonists were deprived of their special legal status and equated with ordinary peasants. Not all Germans liked these changes. Some emigrated to North and South America and did so wisely because the real nightmare began soon after.

Germans During the First World War: Enemies of the People

After the outbreak of World War I, anti-German sentiment in Russia intensified with the German Empire becoming Russia’s main military adversary. The British and French Empires, Serbia, and the Russian Empire fought against the German and the Austro-Hungarian Empires, with other countries joining them later. Propaganda on both sides demonized opponents in every possible way and developed an “image of the enemy” as a cruel, vile, inhuman creature. This happened to the Germans, as well.

A brochure from 1914 entitled “The German” claims:

— He likes to flood the markets with cheap goods of mediocre quality, but he knows the price of everything and doesn’t go after cheap goods..

— The modern German dreams not of God and the Universe, but of armed pogroms..

— The German is swollen with pride for his Kaiser and with contempt for the surrounding Russian environment.

Propaganda attributed the hatred of Russians to Germans. At the same time, it claimed Russia had helped Germany many times, and that Germany practically owed its existence to Russia.

Nationalism, flourishing all over the world, added fuel to the fire. Germans were disliked because they lived in closed, isolated colonies and because they were so widely represented in government and in court. These sentiments existed in society even before the First World War when some called for fighting “German domination”. After the outbreak of war, the press launched an extensive anti-German campaign.

Spy mania developed in the country. As Fourth State Duma Deputy Sergei Shidlovsky wrote, “Every administrator tried to find a German and expel him. German schools and newspapers were closed. In 1915, a decree was issued requiring the compulsory dismissal of all Germans from Moscow enterprises and the closing down of German firms in the city.

German colonists, previously valued for their hard work and integrity, were also affected by this. They were now at best portrayed as rude and ignorant savages, “debunking the myth” of their efficiency. At worst, they were accused of subversion, arson, and attacks on Russian peasants.

St. Petersburg, which associated it with German cities, was renamed Petrograd. Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, German by birth, was accused of having contacts with the “enemy side” and promoting German interests. These were just unconfirmed rumours, but they undermined confidence in the government and contributed to the decline of the monarchy’s authority.

In 1915, the Russian Empire passed laws to alienate land from German and Austria-Hungarian settlers in the western provinces. These laws deprived citizens of German nationality of the right to own and cultivate land within a 150-verst (160-km) strip “along the existing state border with Germany and Austria-Hungary and the area adjacent to this strip”. The ban also applied to a 100-verst (106-km) strip “along the state borders in Bessarabian Province, the Black and Azov seacoasts and their bays, including the entire territory of the Crimean Peninsula, and along the entire state border in Transcaucasia from the Black Sea to the Caspian Sea”. These were exactly where many German colonists lived.

“Subjects of hostile states” were deprived of judicial protection. All Germans whose ancestors received Russian citizenship less than 100 years ago became prisoners of war and were subject to internment — forced detention, resettlement, or other restrictions on freedom of movement. The plan was to deport all Volga Germans to Siberia starting in the spring of 1917. This plan was thwarted by the February Revolution. But — spoiler alert — it was realized later.

Germanophobia in the Russian Empire culminated in German pogroms in 1914–1915. In Moscow, tens of thousands of people attacked stores owned by people with German surnames, setting store windows on fire and looting goods. The largest pogrom, in which more than 100,000 people participated, took place on May 27–28, 1915. Five people of German origin were killed, while 475 commercial enterprises and 207 private apartments and houses were destroyed.

The Volga German ASSR: A German Republic in the USSR

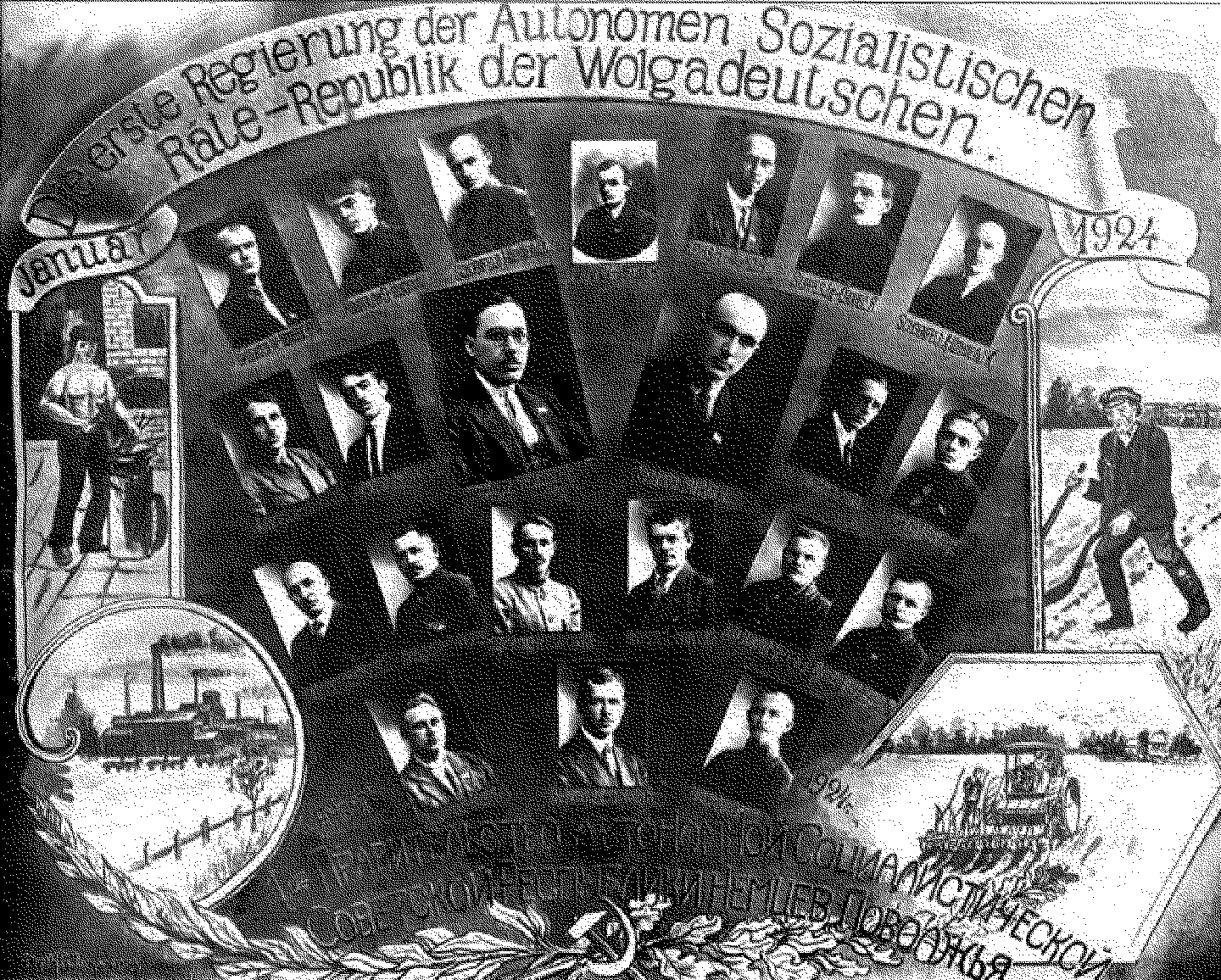

World War I ended and the Russian government changed, likewise changing its attitude towards Germans from “enemies of the people” to “builders of communism”. There was even an autonomous republic of Volga Germans within the USSR, which existed from 1923 to 1941. The German Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR) had a constitution and its own government.

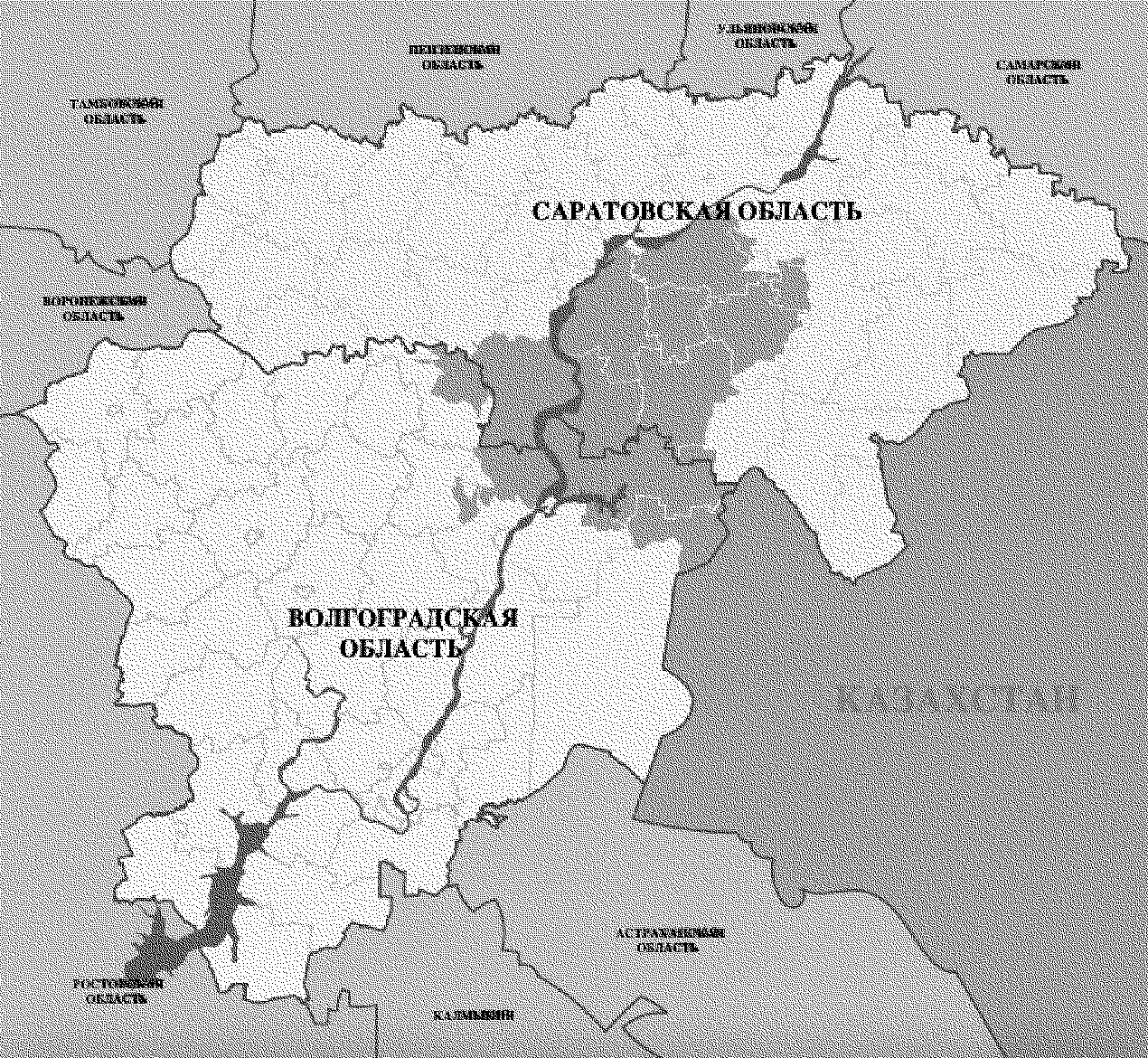

The Volga German ASSR was located on part of what are now the Saratov and Volgograd Regions. It is interesting that administrative units in the republic were called cantons — just like in Switzerland. The ASSR’s capital was the city of Engels — the Germans also called it Kosakenstadt. Although other nationalities lived in the republic, Germans were the majority. According to the 1926 census, of the 571,000 people populating the republic, 66% were Germans, 20% were Russians, and 14% were of other ethnicities. German was the second official language, newspapers were published in German, and schools taught in German.

Not all Soviet Germans lived in the Volga German ASSR. By 1939, there were 1.4 million Germans in the country and only 376,000 of them lived in the Volga region. The rest were scattered throughout other parts of the RSFSR, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Georgia.

Despite the autonomy, life in the Volga German ASSR was not easy. Collectivization destroyed thousands of efficient peasant farms, which were replaced by collective farms. Collective farmers were forbidden from managing their farms or solve their problems independently. They could only fulfil orders from above, which did not always take into account the particularities of locations and the specifics of collectives.

Nearly the entire harvest had to be handed over to the state. In 1931–1933, this led to famine in many villages of the republic. Trying to save themselves from dying, villagers kept what was left of the harvest. In response, the government issued the famous Law on Five Spikelets, which punished people for thefts of even small quantities of grain which was considered “public property”. In the first half of 1932 alone, 32 people were shot and 325 people sentenced to 10 years in prison in the Volga German ASSR under the Law of Five Spikelets.

Autonomy did not last long. In the early 1930s, Stalin began closing German schools, universities, and newspapers, and depriving German the status of an official language. In 1937–1938, all “German subjects” (in reality, just Soviet Germans) working in the defence industry were arrested: 55,000 Germans were convicted, nearly 42,000 were shot, and 13,000 were exiled. With relations between the USSR and Germany deteriorating, ordinary people were thrown under the bus. But this was only the beginning. World War II was ahead.

Germans in the USSR During World War II: Once More “Enemies of the People”

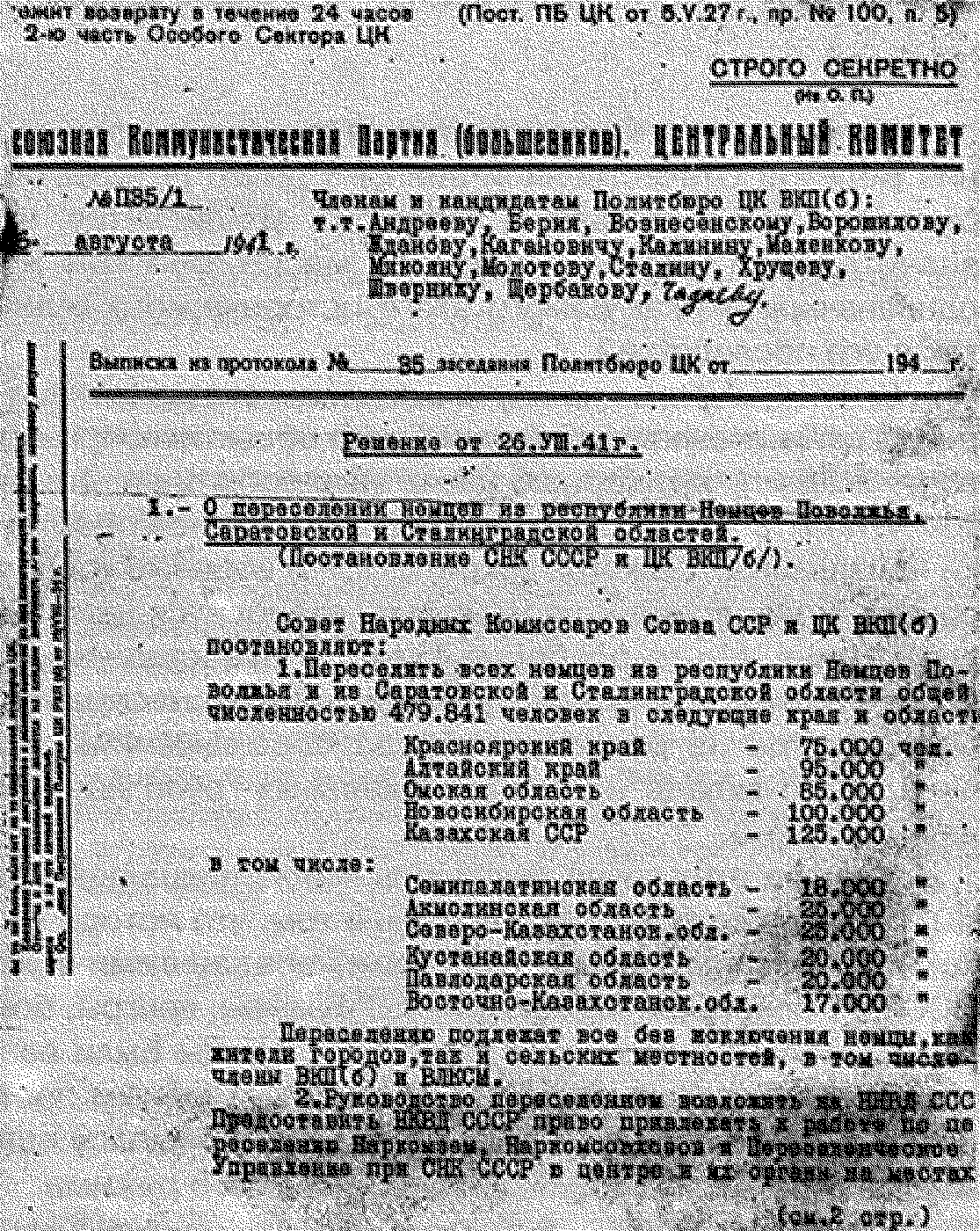

In August 1941, the Volga German ASSR was liquidated. All Soviet Germans were deported to the Kazakh and Kyrgyz SSRs, and to other Central Asian republics, Siberia, and Altai. In all, nearly one million people. As during World War I, the state considered Germans a “security threat” simply because of their ethnicity.

On August 30, 1941, the newspaper Bolshevik explained the reasons for deporting the Germans:

According to reliable data received by the military authorities, there are tens of thousands of saboteurs and spies among the German population living in the Volga region, who, receiving the signal from Germany, must carry out explosions. The presence of such a large number of saboteurs and spies has not been reported to the Soviet authorities by any of the Germans living in the Volga region. This means the German population in the Volga region conceals in its midst enemies of the Soviet people and of Soviet power. In order to avoid undesirable events and to prevent serious bloodshed, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR recognized the necessity of relocating the entire German population living in the Volga region to other parts of the country.

Germans were deported the same way as other Soviet peoples, including Finns, Poles, Lithuanians, Latvians, Estonians, Ukrainians, Koreans, and many others. They had 24-48 hours to pack their personal property, small tools, and food — weighing no more than one ton per family. Evading deportation put people at the risk of criminal prosecution. Most Germans were deported to Siberia, where they worked in factories relocated from the frontline. Deportees did not have enough food or housing. Many had to live in barracks and even dugouts in the ground. Living under such conditions in Siberia’s harsh climate exhausted them and caused mass death.

Why the Soviet Union perpetrated forced relocations of peoples

From 1942 to 1947, Germans aged 15 and 55 were conscripted into a “labour army” to build factories, railroads, and houses, and work in logging and mines. Eduard says, these were really labour camps, where many Germans died of exhaustion, cold, and disease. Eduard's 13-year-old grandmother escaped this fate — she was deported to Kyrgyzstan. But her parents were inducted to the labor army.

Germans in the USSR in 1945–1991: Life in Kyrgyzstan

Germans who survived the war and the labor army could settle only in deportation areas in special settlements. In 1948, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR adopted a decree forbidding Germans from returning to their former places of residence. Germans had to report regularly to the military commandant's office. They were not hired for managerial positions, and it was difficult for them to have a career in state bodies.

The military commandant's office operated until 1956, and the residency restriction in place until 1964. Subsequently, Germans received the right to relocate to their places of pre-war residence. However, many did not take advantage of this, having already settled in new places. This was the case with Eduard's family.

While still young, Eduard's grandmother and grandfather, along with other relatives, were deported to Bishkek. There they built themselves temporary housing and started farming — growing potatoes and strawberries, and later flowers. His grandfather, who had been a German teacher, built a school on Bishkek’s outskirts together with other Germans. Kyrgyzstan Germans were often involved in construction: building dams or working as engineers. Three of Eduard's uncles were architects.

Russian became Eduard’s family’s native language. However, it was important for them to remain German and preserve their traditions and faith. Kyrgyzstan Germans preferred to live as neighbours, maintaining close ties and helping each other. Despite Soviet propaganda of atheism, Kyrgyzstan Germans celebrated Christmas on December 24, as in Germany, and gathered in makeshift home Kirches — they were forbidden from building their own churches. Later, in the 1980s, the Germans were allowed to open their own church in Bishkek.

These days, Eduard's parents communicate with each other in Russian. But all his grandparents spoke the Plattdeutsch dialect. When Eduard's parents attended Soviet schools, they faced language and integration difficulties. Therefore, their families decided to switch to Russian. In this way, they tried to avoid discrimination and become full participants in Soviet society. Despite this, Eduard was called a “kraut”: his ethnicity was revealed by his German surname and his mother’s profession; she was a German teacher.

Eduard has fond memories of life in Kyrgyzstan. His family was friendly with their neighbours, among whom weren’t only Germans, since many other deported peoples lived in Bishkek, including Turks, Kurds, Koreans, and Greeks. He still communicates with and visits some of them.

Eduard says that they moved to Germany not because they were poor in the USSR or had bad lives. They simply felt like strangers and wanted to return to their historical homeland. Despite the fact that Germans formally had equal rights with other Soviet citizens, to some extent, they were still treated as enemies of the people. From the time he was a child, Eduard felt that he was other — not Kyrgyz, not Russian, not Turkish. He always knew he would go to Germany; his family had planned the move for a long time.

Eduard recalls: “We were told that the USSR was the best country in the world. But at the same time, we received information about the 'outside world' from our relatives in Germany, Canada, and the United States. They wrote us letters, sometimes sent us parcels with goodies — it was a holiday. As a child, I wanted to move as soon as possible, but I couldn't imagine that it would actually happen.”

Kyrgyzstan Germans after the USSR’s collapse: Finding a Home

Before the collapse of the USSR, only those Germans with close relatives there — parents, children, brothers, and sisters — could return to Germany. Some of Eduard's relatives already left for Germany in the 1970s and 1980s, but his family was able to move only in 1989. His uncle went to Germany, and from there he was able to invite his brother — Eduard's father — and, with him, his whole family.

Eduard's family managed to emigrate before the USSR’s collapse. Most Kyrgyzstan Germans left for Germany later, during the 1990s. On April 26, 1991, the RSFSR adopted the Law on the Rehabilitation of Repressed Peoples. It recognized the unlawfulness of the policy of arbitrariness and lawlessness applied at the state level to deported peoples.

Today, almost all the Germans have left Kyrgyzstan. According to the census, in 1959, there were almost 40,000 Germans living in Kyrgyzstan. By 2022, 7,886 remained. Among those who continued to live in Kyrgyzstan, many believers remained — Mennonites among them. Eduard recalls that when they moved to Germany, his mother was not used to the German language spoken there. After all, she didn't learn modern German in school. She learned “canned” German in the family, from old books. After living in the USSR, it felt strange to find herself in Germany. As Eduard tells us, “We experienced a strong culture shock. It took time to integrate into German society. It was easier for us as children, but it was much more difficult for our parents.”

Since moving to Germany, the Kyrgyzstan Germans continue to communicate with each other. Eduard's family regularly gets together with their neighbours from Bishkek, who have become almost like relatives. At these meetings, they often cook pilaf and manty in memory of Kyrgyzstan. Eduard is still interested in post-Soviet culture, the culture of Central Asia, and the Caucasus, and he travels extensively in these regions.

I have a map of Bishkek perfectly preserved in my head. Whenever I travel to Kyrgyzstan, I feel nostalgic for the time I lived there and for my native places. A lot of things remain the same as in my childhood, but unfortunately, they cut down a lot of trees in the center of the city.

Kyrgyzstan is a very hospitable country with wonderful people and a unique culture. I am always well received there, invited into yurts, and given food. I have noticed that there is some special kindness in Kyrgyzstan. In a caravan I can travel for long periods of time, get to know the country from a non-tourist perspective, and communicate with the locals.

We used to put up and take down yurts together with the seasonal nomads. It is a very quick process if everyone knows what to do. People have to become nomadic because there are fewer pastures in Kyrgyzstan due to climate change. And in order to have enough space for everyone, people have to climb higher and higher into the mountains in search of pastures suitable for livestock in the face of climate change.

There is still Russian influence in Kyrgyzstan. Young people in the big cities often speak Russian. But I believe that Kyrgyzstan must find its own way. It is a very interesting region with great potential in many sectors.