Editorial note:

Ukraine currently recognises three peoples as indigenous at the legislative level: the Krymchaks, Crimean Karaites, and Crimean Tatars. However, they are not the only ethnic groups whose ethnogenesis happened on the peninsula, as the Urums and Rumeans, or North Azovian Greeks, have also formed in Crimea. The Urums and Rumeans were deported from the peninsula by order of Catherine II. On 9 March 1778, she signed two rescripts ordering the resettlement of all Crimean Christians (Urums, Rumeans, Armenians, Georgians, and Vlachs; 31,386 people in total). The Empress explained this resettlement as ‘helping the brotherly Christian peoples’ in defense against the predominantly Muslim population of Crimea. However, this did not correspond to reality, as the population of Crimea before the first Russian annexation was very diverse, with interfaith, interethnic, and interreligious marriages being formed quite often. Thus, Crimean Muslims also opposed this deportation, as Bohdan Korolenko, PhD in History and a researcher at the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory, notes:

The commander of the Crimean Corps (from March 1778), Alexander Suvorov, who was responsible for the deportation action, wrote on this occasion on 4 August 1778: ‘Things are going on as usual, as if the Tatars, losing their souls from their bodies, did not interfere.’

Thus, numerous Urums and Rumeians were settled in Nadazovia, mainly in the territory of the modern Donetsk region, the largest number (over 21,000 according to the 2001 census) in Mariupol, which was occupied by the Russian Federation in the spring of 2022 and is one of the greatest tragedies of the Russian-Ukrainian war.

Nevertheless, a certain number of Crimean Greeks remained on the peninsula after the deportation of 1778. By the beginning of World War II, more than 20,000 Greeks lived there. The deportation of the Crimean Greeks was prescribed by the Decree of the State Defense Committee of the USSR No. 5984ss of June 2, 1944. were carried out on 27-28 June 1944, and 15,040 Greeks were deported. As a result of additional deportations, 16,006 people were expelled. Also, during the deportation of Crimean Tatars in 1944, several hundred Crimean Karaites were deported along with them, which was a very significant part of the entire Karaite population of the peninsula, as according to the 1926 census, only 4,213 Karaites lived in Crimea.

More complete statistics on the deportations of Crimean residents who were representatives of various ethnic communities, such as Crimean Tatars, Germans, Italians, Bulgarians, Greeks, Armenians, Roma, and others, can be found on the website Crimea. Realities.

A "Special" city

I was born and raised in Sevastopol – a city described as "Legendary Sevastopol" has been the official municipal anthem of Sevastopol since 1994. The chorus of the anthem, which all Sevastopol residents know by heart, sounds like this:,Legendary Sevastopol,

Inaccessible to enemies.

Sevastopol, Sevastopol

The pride of Russian sailors! and Also, words from the chorus of the municipal anthem, “Legendary Sevastopol”, are known to all Sevastopol residents. a city of This city's name appears in many sources (for example, in the titles of books about Sevastopol) and is actively supported by Russian propaganda. and "Russian sailors." I have heard these words since my early childhood, repeated by relatives and teachers, and spoken at every holiday. I saw them in my Since the 2000s, Sevastopol school students have been receiving the "Sevastopol School Student Diary," which they must use. In this diary, the city's history is described with a special emphasis on the heroism of the city's defenders. and on advertising posters. I noticed how, in textbooks, Sevastopol was always mentioned separately, as if we were not in Crimea at all. Friends from other cities in Crimea and Ukraine kept telling me: "You here are different," "Sevastopol has always been special." After 2014, hearing this became even more painful: the city's peculiarity became a justification for the annexation of Crimea. I felt, and still sometimes feel, foreign, different, and special everywhere.

This sense of specialness inspired this text. Its goal is to deconstruct this feeling and understand where it originates, why it exists, and what narratives lie behind it. To do this, I will first explore the narrative of specialness – the meanings behind it and why it is a convenient tool for colonial powers to strengthen their influence and promote their agenda. Then, I will show how and why this narrative became the foundation of Sevastopol residents' identity. Over centuries, Russia has supported and developed this narrative to colonize and russify both the city of Sevastopol and the Crimean peninsula as a whole. Thus, this text is an attempt to decolonize my hometown's history and its identity.

I. How the Concept of Special Works

The concept of special always implies its opposite – something ordinary, even banal and mediocre. Against the backdrop of the ordinary, the special stands out and draws attention. Emotionally, it carries positive connotations, while the ordinary is perceived neutrally or even negatively. All societal rules and norms are written for ordinary people, while the special ones can do anything, even go beyond the law and morality; they are allowed more – they hold greater power. This is why the concept of special is perceived positively and symbolically associated with power and freedom of choice.

Boris Dubin notes that labeling something as "special" – whether a regime, order, department, meeting, or file – refers to mythologized connotations of secrecy[1]. Access to the hidden is another characteristic of the concept of special. Only special ones have the right to know the secret, and this is what reinforces their superiority. Dubin writes[1, p. 42]:

The fundamental unattainability and incomprehensibility of this type of state power is symbolized by its invisibility – or at least by the flagrant limitations to the merely human embodiment of might on such a scale.

Thus, the narrative of specialness often includes significations of the sacred and superhuman. Such power is inherently unattainable for ordinary people, and communication or interaction with it is impossible. This causes a feeling of helplessness among the country's population: for example, this can be expressed in the attitude towards the authorities, as "it is them who decide at the top somewhere there, and we cannot do anything here." This helplessness and inability to participate in society's political life reduces society's interest in political processes, reinforcing the existing social hierarchy.

All these characteristics of the concept of specialness demonstrate that it is filled more with emotion and feeling than concrete meanings. Calling someone or something special manipulates the feeling of belonging to a higher community. This status helps justify any actions of this group, and the intense emotional charge of these concepts helps to form stereotypes and mobilize public opinion in support of specific ideas or actions. In the next section, I will show how this works in the case of Sevastopol.

II. Sevastopol: A Special City

Sevastopol, from its very inception, has been the core of Russia's colonial processes in Crimea and, hence, special. Founded in 1783 on the Crimean Tatar village Aqyar site, the city was originally named Akhtiar. However, this city's name did not fit into the Catherine the Great sought to destroy the Ottoman Empire and divide its territories between Russia, the Holy Roman Empire, and the Venetian Republic. Her global "Greek project" sought to (re)create the Byzantine Empire under the auspices of Russia, but it was never fully implemented. Still, within the framework of this project, Russia conquered Crimea. The official and most common language of Byzantium was Ancient Greek, so the settlements of Crimea were renamed in the Ancient Greek manner. of Catherine The Great and Prince Grigory Potemkin, so in 1784, the city was renamed However, in 1797, Paul I again tried to return the name Akhtiar to the city, but without success: it existed until 1826, and both names were used during this period. (from the Greek Σεβαστός (Sebastos) meaning "venerable" or "sacred" and πόλη (polis) meaning "city"). This new name emphasized the sacred role that the Russian Empire envisioned for it. Moreover, the new name allowed the severing of the cultural and historical ties with the region's indigenous population. They now became "foreigners" and "others" in their own land, while the newly established city became "Russian" and part of the Russian Empire – an "exceptional" part, as the city was destined to protect the empire's southern borders and serve as a base for the Black Sea Fleet.

For this text, I interviewed some Sevastopol residents about their understanding of the specialness of the city and their experience living there. Some of them admitted:

It is strange when I try to break down into blocks the meaning of Sevastopol’s uniqueness, it all seems disconnected and nonsensical. But overall, we all – my friends, my classmates, my circle – felt like we were special.

Original text in Russian: «Так странно, когда я рассказываю, пытаюсь разложить на какие-то кирпичики смысловые, то, из чего складывалась вот эта значимость, уникальность Севастополя и севастопольцев, то получается какой-то бред разрозненный. Но в целом, мы все — моё окружение, мои одноклассники, мои друзья, мы все — чувствовали себя такими».

If you think about the experience of living in Sevastopol, you always hear that you are living in some special place, and you must always remember that. You are constantly reminded of this and, thus, you grow used to feeling special, but you don’t fully understand why.

Original text in Ukrainian: «Якщо так подумати про досвід жити в Севастополі, ти весь час чуєш, що ти живеш в якомусь особливому місці, що завжди от тобі треба весь час пам'ятати, що ти наче живеш в якомусь особливому місці і якось через це ти звикаєш до того, що ти якийсь особливий, але до кінця ти не розбираєшся в чому особливість».

Their confusion and inability to explain their feelings stem from the fact that the concept of specialness is difficult to rationalize. As shown earlier, it is loaded with intense emotions. In Sevastopol, this narrative of specialness permeates every aspect of life: the city’s history, legal status, demographics, and residents' identity. Next, I will analyze each of these aspects separately.

The Special History

Everyone who grew up in Sevastopol, everyone who lives there knows from childhood that Sevastopol is a city of glory, a city worthy of reverence, a city of Russian sailors –exclusively, Russian sailors. It is a base of the Black Sea Fleet – all these designations are very important. This has been ingrained from school, even from early childhood.

Original text in Russian: «[В]се, кто вырос в Севастополе, все, кто там живёт с детства, знают, что Севастополь — это город славы, город, достойный поклонения, город русских моряков, причём именно так — русских. Это город-база черноморского флота, то есть вот эти вот номинации — они прям являются очень значимыми. Со школы, даже с детства».

From a young age, this theme was strong – our grandfathers died for us, our city stood strong and survived (there are a ton of monuments, military objects, and “heroic” places at every step), we don’t surrender to the enemy, we endure any hardship for victory.

Original text in Russian: «С детства была сильна эта тема — наши деды умирали за нас, наш город стоял и выстоял (там же дофига памятников, военных объектов, куча всего “героического” на каждом шагу), не сдаемся врагу, потерпим любые лишения ради победы».

The primary component of the narrative of Sevastopol's specialness lies in its history. The city's ascribed epithets, such as "the city of Russian glory," "inaccessible to enemies," and so on, refer to mythologized events in the city's history, particularly two sieges – during the During the Crimean War, the siege of Sevastopol lasted from October 1854 to September 1855. and During World War II, Sevastopol was sieged in 1941-1942..

These events form the core of the narrative about Sevastopol's sacred role in Russian history and the heroism of its defenders. In Russian historiography, these defenders were, of course, exclusively Russians. The city's history is interpreted through the lens of these two events. However, as Ukrainian historian Serhiy Hromenko notes, the real history of Sevastopol includes The three defenses not included in the Russian canon are:,1) The siege of the city by German troops from April 24 to 28, 1918. The defenders were Red Guards and Black Sea sailors. On April 29, the Bolsheviks began the evacuation, and on May 1, the Germans entered the city.,2) The siege of the city by the Workers' and Peasants' Red Army from April 15 to 28, 1919. The defenders were the French. On April 23, a final agreement was reached, and on April 28, the Anglo-French squadron left Sevastopol Bay for the outer roadstead. The next day, the first Red units entered the city.,3) The siege of the city by the Soviet Army from April 16 to May 9-12, 1944. The defenders were the Wehrmacht. The assault on Sapun Mountain by Soviet troops began on May 7, and on May 9, Sevastopol was taken entirely. After the Germans left the city, the battle began at Cape Khersones, where the Wehrmacht held positions until May 12., none of which were successful – each time the city surrendered to the advancing forces[2, p. 73].

In all five battles for Sevastopol, the defenders never managed to hold the city even once! So the idea of Sevastopol’s inaccessibility exists only in the lines of the anthem and in the imagination of patriotic Russians, while in reality, the city was taken by everyone who wanted it.

Russia's defeat in the Crimean War ended with the signing of the Treaty of Paris, which prohibited the Russian Empire from maintaining military bases and a fleet in the Black Sea. The Russian Empire downplayed its defeat to suppress feelings of humiliation, disappointment, and powerlessness, focusing instead on glorifying the heroism of Russian soldiers defending the Crimea became part of the Russian Empire just 70 years before the Crimean War.. For instance, the Decembrist and traveler Mikhail Bestuzhev wrote in 1856[3]:

Sevastopol has fallen, but with such glory that every Russian, especially sailors, should be proud of this fall, which is worth brilliant victories.

This was the beginning of the narrative of Sevastopol as a special Russian hero city. Simultaneously, this narrative deliberately ignored the fate of the indigenous Crimean Tatar population. The names of their cities and villages, their culture, language, and any connections with Crimea were erased by the Russian Empire. During and after the Crimean War, the Russian Empire gradually distributed the peninsula's lands among its nobles. The conditions created by the Russian Empire forced many Crimean Tatars to leave their homeland, migrating to places like Turkey, where they could freely practice Islam. By 1899, more than two hundred thousand Crimean Tatars had left Crimea. Thus, Russia carried out a settler-colonial policy on the peninsula, populating the lands vacated by the mass exodus of Crimean Tatars with the Russian people. This colonial strategy was successful, as these new settlers became the "local" population of the occupied territory, considered Crimea their homeland, and identified as Russian, thus deeming Crimea Russian as well.

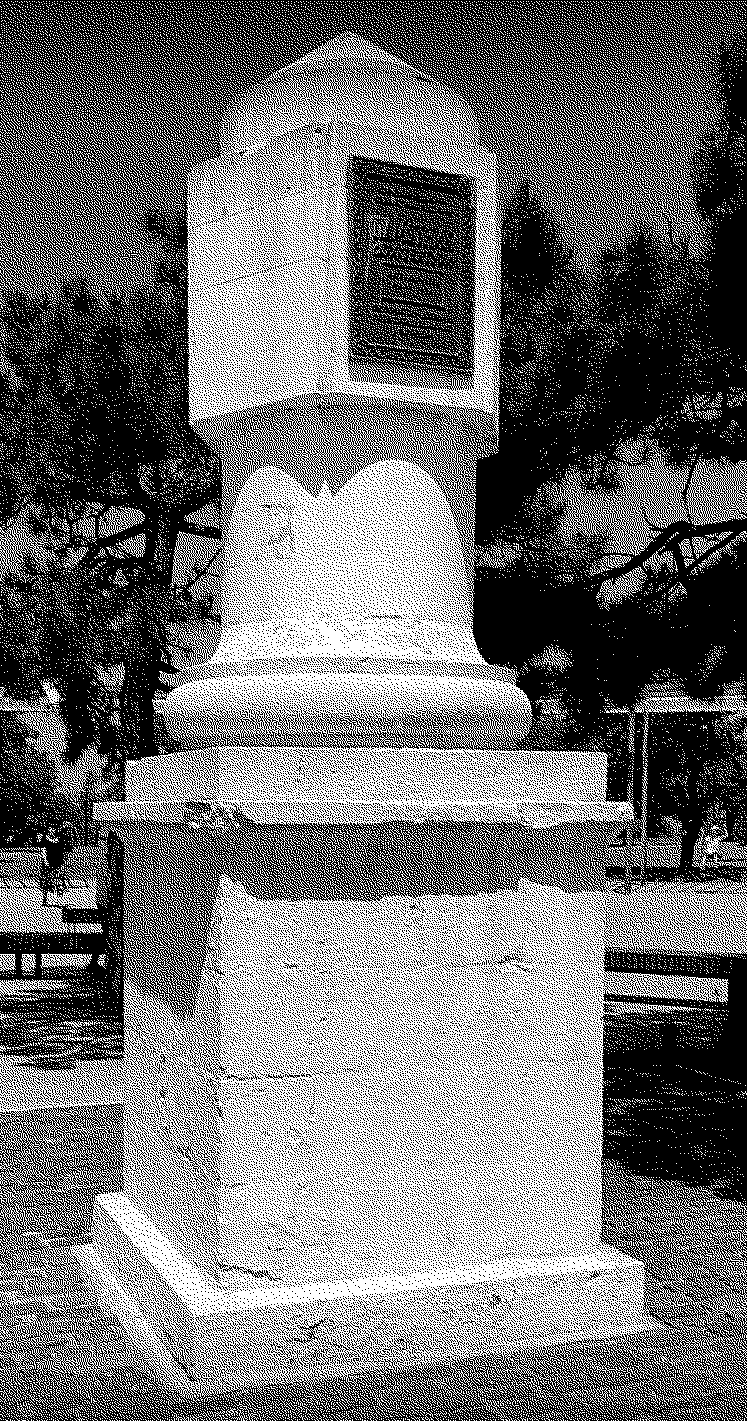

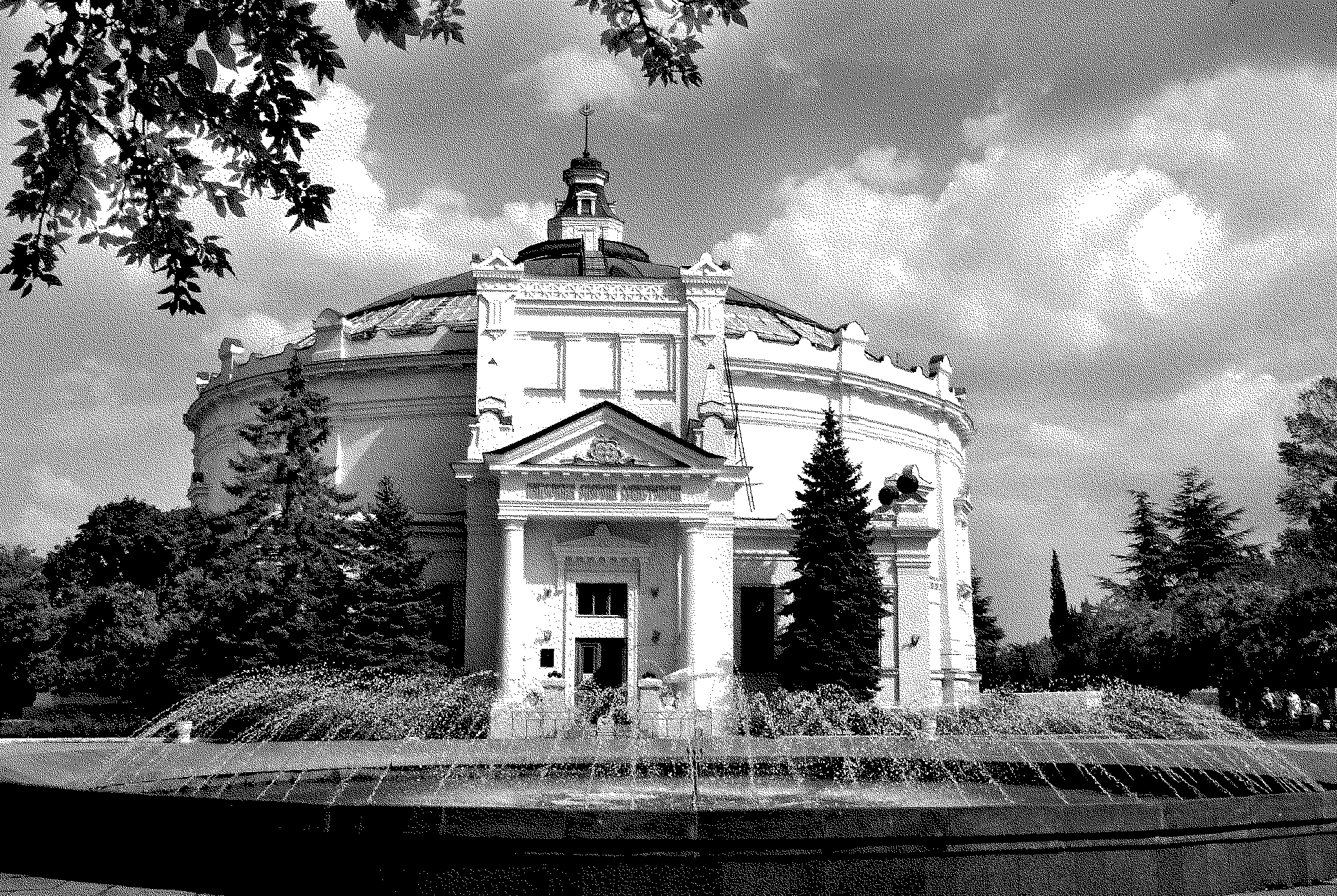

Just fifty years after the Crimean War, the Russian Empire again focused on the narrative of Sevastopol's specialness. The government wanted to distract the population from their defeat in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) and the poverty and internal problems associated with it. The 50th anniversary of the first defense of Sevastopol was marked by the construction of numerous monuments, including the Sevastopol Panorama and the Monument to the Sunken Ships, which later became the city's main attractions. Monuments play a key role in shaping and solidifying historical memory, serving as visual and physical embodiments of symbolic events and their associated ideologies. In the case of Sevastopol, the emphasis on the heroism of the city's defenders helps sustain the myth of invincible Russian might and endurance. It also justifies Russia’s imperial ambitions, as if excusing them by the self-sacrifice of Sevastopol's defenders, while simultaneously erasing any mention of indigenous peoples and the colonial violence inflicted upon them.

World War II brought Sevastopol's specialness narrative to a new level. This time, the heroic myth was revived by Soviet propaganda, which described Sevastopol and its defenders – those who survived another siege in 1941–1942 – as continuing the tradition established during the first defense of the city in the Crimean War. For example, Admiral Pavel Nakhimov, a participant in the first defense of Sevastopol, was elevated to the status of a national hero in 1944. His name was immortalized in Soviet awards, and he became an icon of Soviet heroic mythology, standing alongside historical figures like Alexander Nevsky and Mikhail Kutuzov.

In the same year, 1944, from April 8 to May 12, the Red Army successfully carried out the Crimean Offensive operation, liberating the peninsula from Nazi forces. On May 15, 1944, parades and celebrations were held across Crimea to mark its liberation. However, just three days later, on May 18, the mass deportation of the Crimean Tatars began. It is important to note that the decree for the deportation was signed by Stalin on May 11, practically when the "liberation" operation concluded. The Crimean Tatars were accused of "mass collaboration" with the Nazis. As a result, an entire nation was branded as "traitors to the Soviet homeland," despite the fact that more than 20,000 Crimean Tatars fought in the Red Army and played a significant role in the resistance to Nazi occupation. As per official data, 191,044 Crimean Tatars were deported to remote regions of the Soviet Union – from the Northern Urals to the Central Asian republics. Consequently, almost none of the indigenous population remained on the peninsula. To further erase their memory, the ethnonym "Crimean Tatars" was banned from all official Soviet documents for the next forty years.

The next stage in the narrative’s development occurred with the centenary celebration of the Crimean War and the city’s defense in 1955. These events took place against the backdrop of the Cold War when the former enemies of Sevastopol during the Crimean War – Great Britain, France, and Turkey – had become NATO members and enemies of the USSR. During this period, dozens of books and hundreds of articles were published about the defense of Sevastopol in 1854–1855. A key work was The City of Russian Glory: Sevastopol in 1854–55, by renowned Soviet historian Yevgeny Tarle, published in 1954 by the Ministry of Defense of the USSR. This book combined criticism of the imperialistic nature of the war, based on Marxist theory, with praise for the Russian people. Tarle focused on the role of Russians in defending Sevastopol, erasing the contributions of other ethnic groups. For example, Ukrainians and Belarusians played significant roles in the first defense of Sevastopol – such as Sailor of the Black Sea Fleet, hero of the Sevastopol defense of 1854-1855, participant in the Battle of Sinop., whose surname was Russified to Koshka, and Naval officer, hero of the Russo-Turkish War of 1828-1829, captain of the 1st rank (1831), knight of the Order of St. George. With the rank of aide-de-camp, he was in the retinue of Emperor Nicholas I. He gained wide fame after the 18-gun brig Mercury, under his command, won a battle with two Turkish ships of the line., a Belarusian.

In 1954, Crimea was transferred to the Ukrainian SSR under the following reasoning:

Considering the economic commonality, territorial proximity, and close economic and cultural ties between the Crimean region and the Ukrainian SSR.

According to Ukrainian historian Petro Volvach, this transfer was a necessary measure due to the dire economic situation on the peninsula caused by postwar devastation and the lack of labor after the deportation of the Crimean Tatars, Germans, Greeks, Armenians, Czechs, and Bulgarians (over 300,000 people in total). The settlers from Russian regions who replaced them lacked the skills to manage the agricultural economy in Crimea's steppe zones. In 1956, Khrushchev condemned Stalin’s policies, particularly the mass ethnic deportations. However, while many peoples were allowed to return to their homelands, three groups were forced to remain in exile: the Germans, the Meskhetian Turks, and the Crimean Tatars. To this day, Russian propaganda refers to the transfer of Crimea to Ukraine in 1954 as "Khrushchev's gift," and the Russian population of Crimea continues to regard Crimean Tatars as "traitors" and "bandits."

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the narrative of the special Russian Sevastopol not only survived but was reinterpreted in modern Russia, becoming a key part of nationalist discourse. The fact that Sevastopol ended up outside Russia’s contemporary borders was seen as a For example, the Russian poet Alexander Nikolaev wrote: ,On the ruins of our superpowerThere is a major paradox of history: Sevastopol — the city of Russian glory — Is ...outside Russian territory.,(the translation quoted from Plokhy, Serhii (2000). The City of Glory: Sevastopol in Russian Historical Mythology. In: Journal of Contemporary History 35 (3): 369–383.) that needed to be corrected. Modern Russia has repeatedly declared the "historical injustice" of Sevastopol and Crimea being part of Ukraine in 1991, using narratives of a "Russian" and "special" Sevastopol. These same narratives were employed to justify the annexation of Crimea in 2014, with Russia calling it the "restoration of historical justice" and the "return to the homeland." Thus, the "special" history of Sevastopol has become an important tool for Russia to justify its colonization of Sevastopol and Crimea, allowing it to impose its own culture and identity while attempting to erase local traditions and memory.

The Special Identity and Demographics

There was always attention paid to Russia. We would always celebrate two New Years: first at 11 p.m. for the Russian New Year, watching their president's speech and setting off fireworks, and then at midnight for the Ukrainian one with the Ukrainian president's speech and more fireworks. This was seen as perfectly normal. The city seemed to unite both Ukrainian and Russian identities.

Original text in Russian: «Всегда было внимание к РФ, всегда встречали два Новых Года: сначала в 11 вечера — российский, и смотрели обращение их президента, были салюты, потом — украинский и тоже президент, салют и так далее. И всё это воспринималось абсолютно нормально. Как бы город объединял в себе и украинскую принадлежность, и российскую».

I understand the strong local identity of Sevastopol residents and their desire to distinguish themselves from other Crimeans. Sevastopol residents are like pompous Petersburgers from the south, except instead of dynasties of intellectuals, there are dynasties of military personnel.

Original text in Russian: «С пониманием отношусь к яркой городской идентичности севастопольцев и к их желанию несколько обособиться от остальных крымчан. Севастопольцы — это такие кичливые петербуржцы южного разлива, только вместо династий интеллигентов здесь процветают потомственные военные».

As shown above, Russia has pursued a consistent policy of erasing the indigenous peoples of Crimea, their culture, language, traditions, beliefs, and identity. This policy continued during Ukraine's independence.

Starting in the 1990s, Russia focused on shaping the image of Ukraine and Ukrainianness as something foreign and alien to Crimea. This representation of Ukrainians as "the other" in contrast to "us" – the Crimeans, and especially Sevastopol residents – greatly contributed to the formation of Sevastopol's special narrative. Every pro-Ukrainian cultural or political event in Crimea was framed as "they have come to us." Such formulations performed two important functions. Firstly, they implanted the idea that Crimea was not Ukrainian, as Ukrainians "came to us" from outside, and thus, they facilitated the isolation of Crimea from mainland Ukraine, hindering integration. The second function was to create the image of Crimea as a potential victim of this external threat, which prompted Crimeans to seek protection from Russian authorities, who promised to shield them from "Ukrainian nationalists."

In his doctoral thesis on Russia's colonization of Crimea in the 1990s[4], Ukrainian historian Maksym Sviezhentsev showed that the local newspaper Slava Sevastopolia played a key role in spreading this narrative. It regularly exploited myths about the two sieges of Sevastopol, highlighting the bravery of "ordinary Sevastopol residents" who defended the city, thereby emphasizing the city’s allegiance to Russia and its inseparable connection to the Russian Black Sea Fleet, which was presented as an integral part of Sevastopol's identity. Moreover, these narratives were not only used in articles published on commemorative dates, such as Victory Day (May 9) or the anniversary of the start of the Great Patriotic War (June 22), but were also regularly mentioned in articles on unrelated topics. For example, in 1990, Slava Sevastopolia reported on assistance provided by Sevastopol residents to refugees from Baku who were victims of ethnic violence and framed this event through the lens of the city’s historical memory: the newspaper’s editorial highlighted that Sevastopol, as a "city of military glory," continued the traditions of aid and support established during wartime.

Russia’s control over Crimea’s media and information space countered potential decolonization efforts in Crimea that might have been possible after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the return of the Crimean Tatars to Crimea in 1989. Pro-Russian media of the time were writing about the "atrocities" of the Crimean Tatars during World War II, falsely portraying them as vengeful toward the Russian population and so on. A systematic campaign was launched to amplify the fear of "Crimean Tatar extremism." As a result, when the Crimean Tatars returned to Crimea, their homes were already occupied by settlers, who often viewed them with hostility. When the redistribution of former collective farmlands into private ownership began in Crimea in the 1990s, the Tatars, who had been forced to work in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan during the Soviet era, faced bureaucratic obstacles that prevented them from obtaining their own land. Consequently, the Crimean Tatars were forced to settle on land informally, which authorities called "squatting." Initially, they created temporary tent settlements, then later built permanent homes. The authorities, including the militia and military, and sometimes local residents, hindered these construction efforts, often violently storming the camps (such as the bloody pogrom in the Krasnyi Rai settlement near Alushta in 1992, when 26 Crimean Tatars were taken hostage by the militia). These sentiments later were actively exploited in 2013-2014, when the media spread stories about "terrifying Banderites" allegedly intending to persecute Russians in Crimea and about the Crimean Tatars supposedly assisting them.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, the Crimean media actively described the "Ukrainization" and "Tatarization" of Crimea as something terrible, which would inevitably lead to violence, while the ongoing Russification of Crimea was portrayed as a "natural" process. The choice of such terms is not coincidental: they are tools of propaganda aimed at demonizing the restoration of Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar identities and at concealing real crimes of the past. For instance, the term "Ukrainization" is used to discredit efforts to restore Ukrainian identity after centuries of Russification, while "Tatarization" is used to vilify the return of the Crimean Tatars to their historical homeland and their cultural revival after genocidal deportations. All of this contributed to the further strengthening of Russian identity among Crimeans and Sevastopol residents. As Ukrainian historian Larysa Yakubova observes, after centuries of mass deportation and destruction of the Crimean Tatars, "the postwar ethno-national history of Crimea essentially started basically from scratch. An additional fateful factor was that this process occurred within a Soviet framework during the formation of the postwar Soviet myth about the Great Patriotic War. [...] As a result, throughout the 1940s and 1950s, Crimea developed the youngest territorial community in Ukraine, one that did not arise from a shared historical, territorial, or ethno-cultural background, but was instead the embodiment of a Soviet demographic project."[6]

Therefore, the current special identity of Sevastopol residents is indeed special, but not in the sense that Russia wants to convey. Its distinctive feature lies in its detachment from ethnic roots: Sevastopol was populated primarily by settlers who carried an artificially constructed identity, initially Soviet and later Russian, rooted in the "great imperial" narrative.

An equally important component of the Sevastopol residents' identity is the fact that Sevastopol was a "closed city" for a long time, meaning entry was possible only with a special permit. Initially, Sevastopol was first "closed" in 1916 after the explosion of the Russian battleship Imperatritsa Mariya. During Soviet times, the city was closed to foreigners in 1939 and then again after its liberation from German forces in 1944. After Ukraine gained independence, Sevastopol's closed-city status remained until 1995, when restrictions were lifted to improve the economic situation.

Sevastopol residents often nostalgically recall the times when the city was "closed." Back then, locals with residence permits enjoyed privileges for visiting the city and felt special, and the military and their families, who made up a significant portion of the population, had access to special stores where they could buy rare goods. Moreover, it was much more difficult for unreliable or anti-Soviet elements to enter the closed city, which helped preserve the population's unique composition and mentality.

When the Crimean Tatars began returning to Crimea in 1989, they were also unable to settle in Sevastopol, as access to the city was closed even for other Crimeans. This isolation, reinforced by systematic Soviet ideological conditioning and later by Russian influence, along with the special privileges enjoyed by Sevastopol residents compared to other Crimeans, led to the forming of an artificial identity among Sevastopol residents. This identity was a mix of a sense of their exclusiveness, "Russianness," glorification of the city's military past, and the perception of everything Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar as alien and hostile.

After the annexation of Crimea, Russia further encouraged and cultivated this identity among Sevastopol residents. At the same time, it actively facilitated the resettlement of Russians to Crimea, weakening Sevastopol's ties with Ukraine. According to Russian statistics, by 2018, more than 177,000 settlers from Russia and other CIS countries had moved to Crimea [5]. As a result, the population density in Sevastopol and Simferopol increased significantly. The local population does not always warmly welcome the newcomers, but Russia conducts harsh repressions and suppresses any attempts to express dissent with its policies. As a result, any objective study of the sentiments of Crimea's residents is currently impossible. The Ukrainian Prometheus Security Environment Research Center writes[5, p.121-122]:

One may reasonably call Crimea a region lost to full-scale analytics. Classical research tools, sociological surveys, focus groups, or expert polls do not work there. Without access to the occupied territories, it is difficult to understand the structure of the population, not to mention the prevailing sentiments.

Crimea will have to be rediscovered after the war ends.

The Special Legal Status of Sevastopol

First and foremost, this is evident even at the administrative level. When people speak of Crimea, Sevastopol residents always emphasize that Sevastopol is not Crimea, and this is very important because, when Sevastopol was part of Ukraine, it was a city directly subordinated to Kyiv, meaning it wasn’t part of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea.

Original text in Russian: «Прежде всего, это проявляется даже на уровне административного деления. Когда люди говорят о Крыме, то все севастопольцы всегда подчёркивают, что Севастополь — это не Крым, и это очень важно, потому что, когда Севастополь был в составе Украины, ну как бы фактически, Севастополь был городом прямого подчинения Киеву, то есть он не относился к Автономной Республике Крым».

The special status of the city manifests, among other things, in its administrative structure – both in Ukraine and in Russia (if I’m not mistaken, Sevastopol officially became a separate region in 1996).

Original text in Russian: «Особый статус города проявляется, помимо всего прочего, в его административном устройстве — что при Украине, что при России (если не ошибаюсь, официально Севастополь является отдельным регионом с 1996 года)».

When discussing the narrative of special Sevastopol, it is impossible to ignore another important component of it – its legal status, which Sevastopol residents themselves like to remind us of, emphasizing the city’s exclusivity.

Since Sevastopol was built as a naval base, its legal status has always stood out in the legal framework. Just four years after its founding, in 1787, the city was designated as a naval base directly subordinate to Saint Petersburg and became a The city was governed by a naval administration appointed directly from St. Petersburg, and at the head of the city was a governor-general, who also commanded the Black Sea Fleet.. In 1804, Sevastopol was recognized as the By the decree of Emperor Alexander I to the Governing Senate of February 23 (March 6), 1804. and commercial ships were prohibited from entering the port. During the Soviet period, despite administrative changes, Sevastopol retained its strategic significance: in 1948, it was separated into an independent administrative and economic center. Russia manipulates this fact, emphasizing Sevastopol’s special status and even attempting to challenge the city’s affiliation with Ukraine on this basis. However, as researchers from the Prometheus Security Environment Research Center note, the 1948 decision did not create a separate administrative-territorial unit for Sevastopol, as the terms "independent administrative and economic center" and "the city of republican subordination" were not defined in Soviet legislation. Sevastopol remained part of the Crimean region, and in the 1954 decision on the transfer of Crimea to Ukraine, Sevastopol was mentioned alongside other cities in the region[5, p.34-35]. Moreover, in the 1978 Constitution of the Ukrainian SSR, Sevastopol was mentioned alongside Kyiv, while the Constitution of the Russian SFSR listed only Moscow and Leningrad. In 1991, the residents of Sevastopol voted in favor|voted-favor of Ukraine’s independence, and in the 1992 Constitution of the Republic of Crimea, Sevastopol was recognized as part of Crimea.

Problems with Sevastopol’s status began after the collapse of the Soviet Union. In December 1992, the issue of Sevastopol's status was raised at the VII Congress of People’s Deputies of the Russian Federation. On July 9, 1993, the Russian Parliament adopted a resolution confirming Sevastopol's "Russian federal status" and instructed the Russian government to negotiate it with Ukraine. However, the deputies’ initiative countered Yeltsin’s policies during the ongoing negotiations with Ukraine about the Black Sea Fleet, so it was not implemented[5, p.34-35]. On July 20, 1993, Ukraine contested the resolution on Sevastopol during a UN Security Council meeting, where Russia’s representative, Yuli Vorontsov, conveyed Yeltsin’s statement that he was ashamed of the actions of Russian deputies. Ultimately, the UN Security Council reaffirmed its commitment to Ukraine’s territorial integrity and declared the Russian Parliament’s resolution invalid.

Sevastopol was granted the title of a "city with special status" within Ukraine, alongside Kyiv, as stated in the 1996 Ukrainian Constitution. This status has remained unchanged, although discussions about its removal periodically arise in Ukraine. However, after the 2014 annexation of Crimea, Russia designated Sevastopol as a "city of federal subject significance," on par with Moscow and Saint Petersburg.

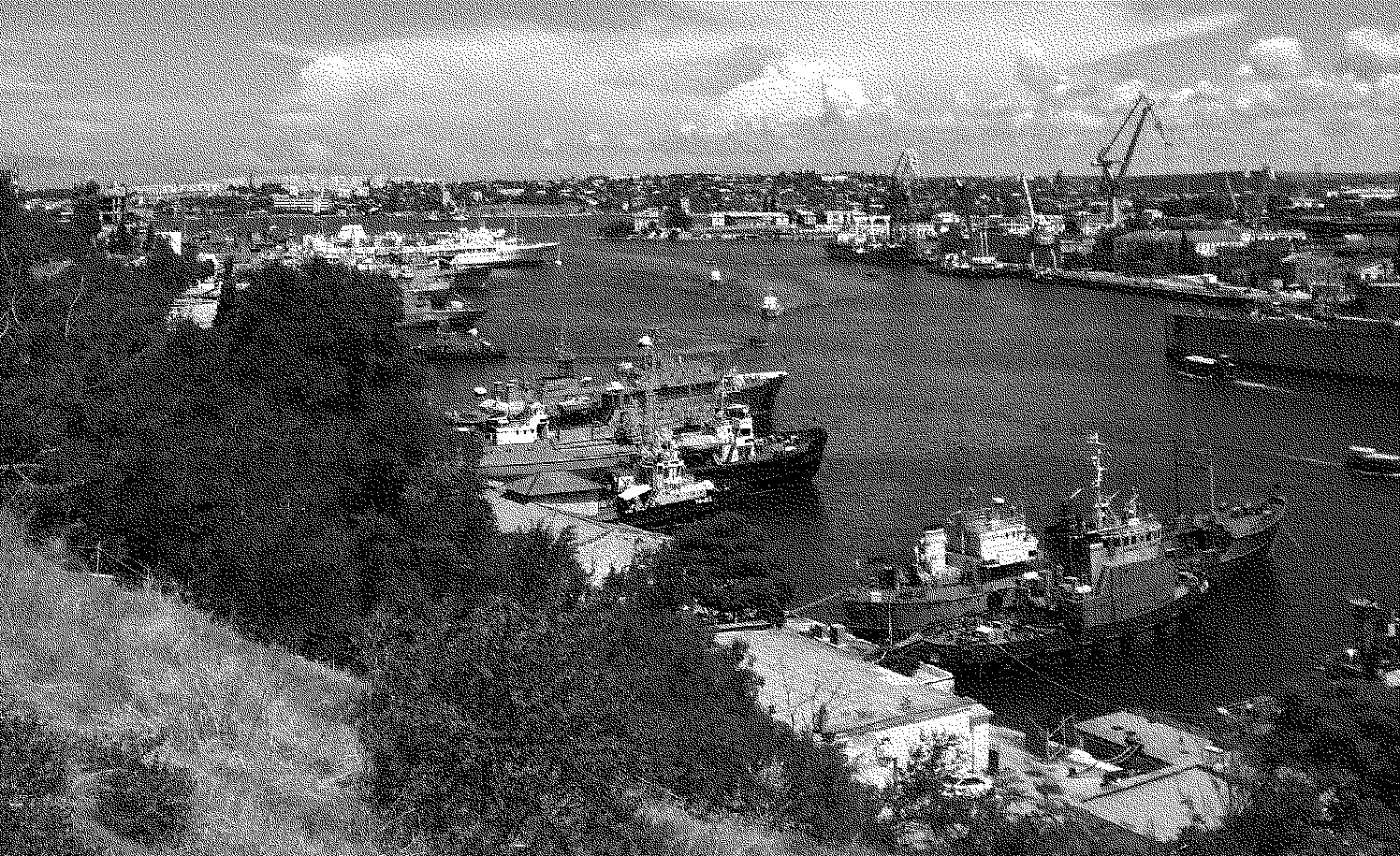

Russia has used the special legal status of Sevastopol throughout history to legitimize its territorial claims and strengthen its military presence on the peninsula. Disputes over the city’s status began due to the protracted and complex negotiations concerning the Black Sea Fleet's division following The Soviet Navy was stationed on the territory of most of the Union republics. The question of its fate outside of Russia was resolved in different ways: by withdrawing the naval forces to the territory of the Russian Federation (as happened in Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania), dividing the fleet between the Russian Federation and the newly independent republic (as happened in Azerbaijan) or legalizing the presence of the Russian Navy on the territory of a post-Soviet republic (in the case of Ukraine).. Russia did not want to lose the fleet and its bases on Ukrainian territory, as this would diminish its influence over Ukraine’s policies. Meanwhile, Ukraine sought to gain control over the Black Sea Fleet, as its primary base was located in Sevastopol, on Ukrainian soil.

In 1992, the first large-scale actions by Russia against Ukraine began, aimed at preventing the transfer of part of the Black Sea Fleet to Ukrainian control. When the 880th Separate Naval Infantry Battalion swore allegiance to Ukraine, the Russian command immediately ordered its dissolution and intensified staffing the fleet exclusively with Russian servicemen. In July 1992, a Russian assault combat group seized the military commandant’s office of the Sevastopol garrison after its personnel swore an oath of allegiance to Ukraine. The conflict culminated with the defection of the patrol ship SKR-112 under the Ukrainian flag to Odesa, accompanied by attempts from the Russian fleet to stop it by force[7]. In 1993-1994, Russia continued provocations by supporting separatist sentiment in Crimea. In response to Russia’s actions, Ukraine was forced to send large numbers of National Guard troops and border guards to Crimea. Eventually, the fleet division In exchange for 31.7% of the fleet (out of the Ukrainian share of 50%), Russia pays off $526.509 million of Ukraine's national debt. The agreement on the Russian Black Sea Fleet basing on Ukrainian territory is valid for 20 years with automatic extension for five-year periods, if the parties agree. The annual repayment of part of the Ukrainian national debt for the basing of the Russian Black Sea Fleet in Ukraine is $97.75 million.. Russia received most of the fleet and signed an agreement to lease bases in Crimea until 2017 in exchange for reducing part of Ukraine’s national debt. During the presidencies of Leonid Kuchma and especially Viktor Yushchenko, Kyiv made it clear that it intended to terminate the lease of the Russian Black Sea Fleet by the agreed deadline. However, Russia showed no intention of preparing to withdraw the fleet and displayed confidence that the Black Sea Fleet would remain in Crimea. The situation changed with the election of the pro-Russian president Viktor Yanukovych. Under the 2010 Kharkiv Agreement, the lease of the Russian Black Sea Fleet in Crimea was extended until 2042 in exchange for a discount on natural gas prices. Following Russia’s seizure of Crimea in 2014, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs terminated the 1997 and 2010 agreements. Ukraine, for its part, did not terminate these agreements, considering their preservation useful for future legal proceedings against Russia in international courts.

The Russian Black Sea Fleet has undoubtedly significantly influenced public life in Crimea, especially in Sevastopol, and continues to do so. The salaries of Russian military personnel have always far exceeded the city’s average income. In the 1990s and 2000s, many retired officers of the Black Sea Fleet chose to stay in Sevastopol. Throughout the same period, Russian propaganda claimed that the Black Sea Fleet was the main economic pillar of Sevastopol, and without it, the city could not survive. However, as the Ukrainian Prometheus Security Environment Research Center noted, the actual situation indicated a gradual decline in the fleet’s economic role as the service sector in the city grew, and investments flowed in from various sources. Moreover, the fleet had chronic debts to construction workers, tax authorities, and utility payments[5, p.51-52].

Russia has historically used the Black Sea Fleet to reinforce the narrative of Sevastopol's "Russianness" and continues to do so today. In the 1990s, the fleet installed monuments related to Russian history, managed cultural and educational institutions – such as assembly halls, museums, libraries, the drama theater, kindergartens, and schools – and, in 1999, constructed buildings for a branch of Moscow State University on the grounds of a military base. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, Sevastopol also celebrated holidays tied to the Russian Navy, with the most popular being Navy Day, celebrated on the last Sunday of July. Celebrations always included military parades, live-fire drills, and demonstrations of special unit capabilities. On several occasions, Russian presidents personally attended these military parades, underscoring the inseparable connection between Sevastopol and Russia.

The Black Sea Fleet also influenced Crimean politics by supporting pro-Russian activists and political groups in the 1990s and 2000s. For instance, the fleet’s printing press produced openly anti-Ukrainian and separatist materials. Furthermore, fleet officers provided classified (including intelligence) information to activists from pro-Russian organizations[5, p.53].

Throughout history, Russia has actively encouraged Sevastopol residents to emphasize their uniqueness, as it put into the narrative of specialness a separation from Ukraine but not from Russia. Moreover, Russia crafted the narrative that Sevastopol was integrated into the Russian cultural and historical space, making the city special because of this connection. Thus, Sevastopol’s special legal status has benefited Russia, as it not only reinforces the idea of the city's exclusivity but also serves as a tool for forming an alternative identity incompatible with Ukrainian and even Crimean identities.

Conclusion

Sevastopol is the core of Russia's colonial policy in Crimea, a policy it has pursued for centuries. This policy is built on a multi-layered, artificially constructed narrative that Sevastopol is a special city. From the city’s founding, Russian propaganda has rewritten its history to solidify and strengthen this narrative.

The identity of Sevastopol residents is detached from ethnic roots and is a mixture of imperialist and Soviet myths. The city's closed legal status also contributed to forming a special demographic consisting primarily of Russian military personnel and those loyal to Russian rule. Everything Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar in Crimea, particularly in Sevastopol, was portrayed as hostile and foreign.

In contrast to all these, I always emphasize that I am Ukrainian, a Crimean, and a Sevastopol resident. Russia has spent centuries trying to erase this identity of mine. To resist this, it is essential to deconstruct the narratives that Russia uses for its colonial purposes and to show that they are artificial.

This work began for me with the study of my family history. My grandparents moved to Crimea in the postwar years from Buryatia, Chuvashia, Siberia, and the Ukrainian Donetsk region. They all became Crimeans and some of them Sevastopol residents. All of them unknowingly became tools of the Russian Empire in its desire to destroy the indigenous population of Crimea and colonize the peninsula. Some of them adopted the special and artificial identity that I am exploring in this text and forgot their roots. However, some did not forget and passed that memory on to me. Thus, having found themselves in Crimea, on the lands of the deported peoples, they — also displaced settlers — sought to learn about the history of Crimea not from official sources but from the personal stories of their neighbors, friends, colleagues, and everyone they met. In this way, they developed another identity — one of their own, complex and multi-layered. Their experience helped me realize the importance of remembering one’s roots and researching one’s family history — not only to avoid becoming a hostage to someone else’s narrative but also to understand from where and how we got here. Discovering how my own family came to Crimea was a key moment in understanding the region’s complexity and the historical processes that have shaped its present.

I hope that Crimeans and Sevastopol residents who are not indigenous to the peninsula will also explore their family histories and, instead of embracing the identity imposed by Russia, will discover their own — one free from externally dictated roles. This identity may be complex, multi-layered, and even uncomfortable, but it marks the beginning of a challenging yet necessary journey toward decolonizing our thinking and understanding of Crimea.